Comparing the ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS 2nd Edition game to the first edition (now over 15 years old!) is like comparing a Porsche 959 to a Model T Ford. Both are great cars for their times, but which would you want to drive in the 1990s?

—Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition Preview, Dragon #142 (February 1989)

In parts one and two I covered the evolution of the adventure module and the changes brought about by the introduction of skill systems and universal task resolution to D&D. By this point I hope it's clear that, regardless of (and indeed, in spite of) the rules framework the game was operating under, by 1989 the supported playstyle at TSR had moved in a very different direction from where it began in the early 1970s. We can't actually know to what degree this reflected the desires of the player base for something different after years of the original style and to what degree it was pushed by the designers and editors themselves, who oversaw TSR's module and rulebook output and selected what appeared in its house organ, Dragon magazine. All available information indicates that TSR's game-related sales began steadily dropping after 1984, but how much of that was widespread dissatisfaction with D&D abandoning its roots and how much of it was the natural collapse of what was to some degree a fad we can't know.[1]

This week I want to tackle 2nd edition itself: what the new edition was meant to be and what specific changes were made in that ruleset that moved it from 1st edition's old-school foundations.

| ||||

| Dragon #142 | |

The New AD&D 2nd Edition is a giant stride forward from the first game. Experienced players will find all the rules they've grown accustomed to. New players will discover a more complete and easier to understand set of rules.

—Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition Preview, Dragon #142

There are many changes between 1st and 2nd edition, many more than is usually noted. At the same time, many of them are subtle ones. Ultimately, this is an article focusing on the shift away from the old-school playstyle, and as such I'm going to detail only those rules changes that affect that. So while, for example, the alteration of the bard, or the removal of artifacts from core, or the elimination of the monk and assassin are all notable changes, the game isn't any more or less old school because of them. If you want just a changelog, I've assembled one over the years compiled from various sources and my own observations: you can get it at this link.

Flavour and Guidance

The Dungeon Master's Guide, of course, contains extensive articles on how to conduct a game (2nd Edition is a major improvement over the first edition in this regard)

—Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition Preview

Over and above rules changes, there is a strong flavour argument to the 1st vs. 2nd edition wars. A common charge is that the 1st edition ruleset is more evocative than the 2nd edition. In the new DMG, David Cook, Steve Winter, and Jon Pickens (the main developers of 2nd edition) wrote in a far less evocative fashion than Gygax. I suspect, however, that they would have worn this as a badge of pride, in that crafting accessible rules requires accessible writing, and ease of access was clearly one of 2nd's goals. For every player I have seen complain that the prose of 2nd is bland (comparatively or otherwise), I've seen another grateful that they can parse a rule quickly in mid-game instead of wading through statements like "perforce, as the killing of humans and other intelligent life forms for the purpose of profit is basically held to be the antithesis of weal."

But while one's preference for the functional vs. the evocative in rules text is subjective, there is a certain amount of crossover into content. On page 7 of the 2nd edition DMG was a section titled "The Fine Art of Being a DM".

Being a good Dungeon Master involves a lot more than knowing the rules. It calls for quick wit, theatrical flair, and a good sense of dramatic timing, among other things. Most of us can claim these attributes to some degree, but there's always room for improvement.

Fortunately, skills like these can be learned and improved with practice. There are hundreds of tricks, shortcuts, and simple principles that can make you a better, more dramatic, and more creative game master.

But you won't find them in the DUNGEON MASTER Guide. This is a reference book for running the AD&D game. We tried to minimize material that doesn't pertain to the immediate conduct of the game.

Much of what's relevant to running an old-school game is found in the 1st edition DMG's "Campaign" chapter. Portions of that chapter could still be found scattered throughout the 2nd edition DMG, but much of it was cut, and the 2nd ed DMG has no dedicated campaign-running chapter of its own. Some of the key 1st edition "flavour" material that was removed was:

|

| 1st edition DMG's sample dungeon |

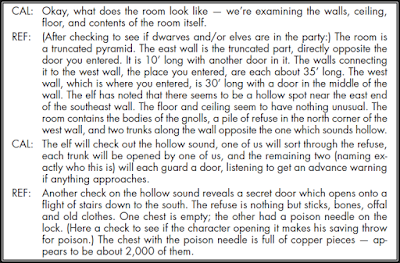

2) The First Dungeon Adventure (pp. 96-100): Immediately after the above is a lengthy example of play, and notably it's centred around dungeon exploration. It explains such vital concepts as adventure setup, NPC roles, and how to describe things as a DM. It breaks out key concepts into subsections (Movement and Searching; Detection of Unusual Circumstances, Traps, and Hearing Noise; Doors). It adds a "live" example of play, written in narrative voice, in which a DM and a party engage in a game, with march order discussion, searches, and a combat all occurring. There is a much smaller (not quite a page) and simpler equivalent in the 2nd edition PHB, but, appearing as it does in that book rather than the DMG, and at the very start (and so by necessity quite simple), it's nowhere near as useful for a DM aiming to figure out how to run things.

In neither DMG is there an encouragement to tightly restrict the movements of the players to best suit the story the DM is trying to tell. However, the 1st edition version, through its example of play, describes how the ideal DM is prepared for the example scenario it helpfully lays out:

Before you are three maps: a large-scale map which shows the village and the surrounding territory, including the fen and monastery, the secret entrance/exit from the place, and lairs of any monsters who happen to dwell in the area; at hand also is a small-scale (1 square to 10’ might be in order) map of the ruined monastery which shows building interiors, insets for upper levels, and a numbered key for descriptions and encounters; lastly, you have the small scale map of the storage chambers and crypts beneath the upper works of the place ... likewise keyed by numbers for descriptions and encounters. So no matter what action the party decides upon, you have the wherewithal to handle the situation.

A proper DM is thus shown to be one who has prepared enough material ahead of time to allow the players to wander to some degree. Both editions emphatically insist that a DM must be prepared to wing it, but only the 1st edition version provides the foundations of dungeon crawling the game was originally built to enable, and emphasizes player freedom in this particular fashion.

Today this shunting of advice off from, say, an OSR rules reference makes more sense, in

that there's a mountain of third-party advice—primers, blogs, forum

posts—available online (although I think a clone should at least include

advice about how to accommodate it and its changes specifically with

the wider world of old-school play, but that's a topic for another

time). But in 1989 (unless you were one of a handful of people able

to access Usenet), your advice was limited to whatever your local fanzines and the Dragon magazine Forum column—if you could get these—were discussing this month, and so this choice was crippling if you were in search of specific playstyle guidance. You had the rules, but large parts of how to apply them were missing.

keep in mind that the PCs are supposed to be heroes. They are unusual persons whose skills and abilities stand head and shoulders above the normal man (figuratively speaking in the case of dwarves and halflings).

They should be able to perform heroic actions without worrying about the fussy details of their activities. They should be concerned with finding lost artifacts, slaying horrible fiends and saving the world; not cleaning their swords after each battle, counting the arrows in their quivers or telling the DM exactly how they prepare for sleep each night. (DMGR1 pp. 36-37)

If the DM can bring himself to think of his campaign as a story with an unwritten ending, he has made the first logical step in successful campaign design. Players, regardless of type, want to do more than just slay endless streams of monsters or loot bottomless treasure hoards. They want to be heroes who perform legendary deeds like the characters in fantasy fiction or film. (DMGR1 pp. 85-86)

Eventually, the encounters should serve to point the adventurers towards what the DM has determined to be the climactic encounter of the adventure. (DMGR1 p. 90)

Mechanics

While the 2nd edition rulebooks cut key bits of old-school-related guidance, there are also noticeable drifts away from the older style of play of a mechanical nature. Some of these are small. The default roll to find secret doors was left out (1 on 1D6), which along with the absence of the ten-foot pole from the equipment list may suggest how much dungeoneering was done during playtesting.[6] Encumbrance was made an optional rule (it already was in B/X, though that was an introductory-level game, and in any case it wasn't optional in the equally introductory BECMI), but even then, there's no weight value for a week of rations, an essential for wilderness adventuring.

Others were more important. The movement rate inside dungeons became ten time greater (from 120 feet per turn to 120 feet per minute), which made the exploration and clearing of dungeons a much quicker thing, while at the same time the recommended wandering monster rate dropped from 1 in 6 every 3 turns to 1 in 10 every 6 turns: about a two-thirds decrease (and when coupled with the fact that a group now raced through a dungeon ten times as fast, resulted in an even greater effective decrease).[7] Non-weapon proficiencies were included in core (albeit still optional), as I covered in part two. And for all that 2nd edition has a reputation of streamlining material,

the Reaction Table (as I explored previously) was only made clumsier in

2nd, expanded to a 2D10 4-column monstrosity. The table also rewards an aggressive style of play, by assuming that

hostility is the

"good" result. That is, hostility is the highest result,

so that any positive table modifiers (except from Charisma, which was reversed) the party manages to accrue leads the players towards it. This

is true even if the players want to be friendly: a friendly approach

only reduces the range of possible hostile results.[8]

The most significant change by far, however, was the shunting of gold for XP to optional status. What causes a PC to level up is the fundamental driver of gameplay across the board, and thus shapes the entire game. A great deal of 2nd edition was optional, so this change is in part deceptive (as I covered in Part II, one of the major design directions of 2nd edition was to make as much optional as possible, to enable a DM to built their own game out of a toolkit). However, the game does list a number of default, official methods of earning XP. Defeating enemies is the one most clearly articulated,[9] but this is supplemented by a bewildering array of additional approved methods: a variable story-based award arbitrated by the DM, an award for surviving, and awards for making the game fun, creating magic items, and for player (not PC) improvement. An optional individual XP award system was added as well, which if used could give awards for behaving in a class-appropriate way, good roleplaying and so on. Amongst all this was the gold-for-XP option, for the group as a whole and/or for rogues at a double rate (2 XP per 1 GP), as the DM felt appropriate. In terms of actual support for the game, things proceeded along the primary lines suggested in the DMG, and while plenty of 2nd edition products awarded handsome treasure hauls, I'm aware of only two products—1995's underworld crawl Night Below and 1999's deliberate throwback module Return to the Keep on the Borderlands—that suggested XP be earned from gold, in keeping with that rule's optional nature.

The "story award" was nebulous: all the DMG really suggested was that it be for completing the adventure, and that it shouldn't outweigh what was earned by defeating foes that adventure, emphasizing the primacy of combat. This story award was implemented in a spotty fashion in official modules (as were all the non-combat methods, official or not). It's difficult to examine the 2nd edition module lineup as a whole: well over 100 modules were released in its 10-year lifetime, so I hope you'll forgive my random cherry-picking (and feel free to point out anything interesting you notice in one). In some cases the story award was used: for example, in 1993's GA3 (Tales of Enchantment) we have elaborate guidance at the module's conclusion:

Any solution that leaves Gwellen and Barens together deserves some award.WGR6 (The City of Skulls) had a similar set of rewards, but overall this level of specificity was the exception, rather than the rule. The predecessor module in the GA series (GA2 Swamplight), released the same year as GA3, had no such awards stated, merely a quick note on the first page that "the PCs should get additional experience points if they find the real menace in the adventure and defeat it. The amount of experience awarded is left up to the DM." 1999's Against the Giants: The Liberation of Geoff gave a simple 25,000 XP award for completing the story goal, while 1996's The Rod of Seven Parts suggested 75-100,000 XP each time a segment of the titular artifact was recovered, and one other reward for defeating the Chaos lord at the heart of the module (50K for imprisonment, 100K for slaying her).

Any solution that returns Barens to Jareb deserves some award, as that was the PCs' mission.

Any solution that allows the pixies' harassment campaign to continue should receive only half XP awards.

Any solution that doesn't return Barens to Jareb should receive only half XP awards.

Any solution that starts a war between the pixies and the "large folk" deserves no award or a negative award based on the other circumstances.

Any solution that pleases everyone deserves at least 10,000 XP, and even more if the players are particularly creative or role-played particularly well.

Any solution that allows Gwellen and Barens to marry and live together happily as man and wife deserves a bonus award of at least 10,000 XP.

Many modules did not bother awarding the story award at all. This includes most of the modules released in 1989 to support the new edition. 1989's FRE 1, 2, and 3 (the godawful Godswar trilogy for Forgotten Realms) had none. The infamous initial Greyhawk trilogy of 1989 (WG9, WG10, and WG11) were refashioned older RPGA modules, but they had no awards added as part of their polishing up for wider release as part of the new edition. 1990's WGA1 (Falcon's Revenge) and WG12 (Valley of the Mage) and 1991's WGS2 (Howl from the North), all-new Greyhawk works, also had none; neither did 1990's LNA1 (Thieves of Lankhmar) or 1992's LNQ1 (Slayers of Lankhmar). Again returning to the GA series (and also 1993), GA1 The Murky Deep gave no special awards or even the suggestion of them. Leaping forward, 1998's The Shattered Circle and The Lost Shrine of Bundushatus worked the same way. While the RPGA generally emphasized role-playing, its 1997 module The Star of Kolhapur and its 1999 module The Wand of Archeal (to pick a random pair) also had none.

More often seen was the individual XP award, despite it being optional in the DMG. For example, while FRE3 had no story award, it does suggests an unspecified XP award for any character who can "orate exceptionally well" in front of the master of the gods (the players can have no effect on what happens at that point, regardless of what they say, but that's neither here nor there). 1995's The Return of Randal Morn grants a mighty 100 XP bonus if the party attacks a catapult as their first target in the climatic scene (but has no story award, despite being the culmination of a linked module trilogy). In 1998's rework of Destiny of Kings, the character that defeats the enemy in a joust to conclude the adventure receives 1,500 XP.

For all that old-school D&D is often depicted as a hack-and-slash game, gold for XP produces a clear gameplay incentive based on wealth, not slaughter. Combat did give XP in 1st edition and Basic, and was often the gateway to the treasure you needed, but the main avenue of advancement was loot, which—when coupled with the dangers inherent to low-level combat especially—often inclined players to avoid battle, not seek it. With 2nd edition, power instead was best earned at the point of a sword. There were other means of gaining XP, as we have seen, both standard and optional, but combat was suggested as the best source and the one actually implemented in 2nd edition products; the clear itemized XP awards for combat laid out in the Monstrous Compendium entries were simple to use, vs. the "figure it out yourself" approach of the other awards. Wealth as a major aspect of D&D gameplay in any fashion increasingly became vestigial.[10]

Overall

I hope these first three articles have managed to explain how D&D changed by the time 2nd edition launched and, from there, why some people don't consider 2nd edition to be properly old school.

For those coming to D&D long after AD&D of any stripe was a going concern, there's little on the

surface to differentiate 1st from 2nd, and this is the source of a lot

of the confusion over 2nd edition's status. Broadly, those who were around for 1st edition's original lifecycle are

the ones most likely to consider 2nd edition not old school,[11] while those

who started with 3rd edition or later are separated from the

controversies and arguments of the time and also have such a radically

different starting point that they're more willing to accept 1st and 2nd

as two sides of the same coin. This is why you find the old school defined

as both "pre-1984 D&D" (a date chosen due to the year Dragonlance came

out and the lack of anything exceptional released otherwise; a definition focused on playstyle) and "pre-3rd

edition D&D" (1974-2000; a definition focused on mechanical compatibility).

If your sole criteria is the core ruleset (i.e. leaving out the later support materials, which of course no one need buy or use), then it's simple to consider 2nd edition just as old school as 1st, as the differences are seemingly minor if your starting comparison point is a later edition or something non-D&D entirely. Most of these can be changed easily enough (though the move away from gold for XP does require using the 1st edition monster manuals rather than 2nd-ed equivalents, because 2nd rebalanced all their monster XPs and the treasure types they would give so that combat was the real reward and treasure a minor concern).

But if considering playstyle, which is fundamentally shaped by a few rather specific and important ruleset changes, it's clear that 2nd edition offers almost nothing along old-school lines, and in fact a decent amount that runs counter to it, especially if you take into account the edition as a whole (its supporting materials). If you're attempting to develop an old-school style of play on your own, you might be able to do so reading 1st edition and earlier (might: the vagueness on this core subject even in the original rulesets means you can easily wind up developing alternate styles as well, as so many did back in the day). However, you'll almost certainly never develop such a style if starting with 2nd edition, because that edition had almost no interest in teaching or supporting an old-school style of play.

That having been said, can you run an old-school game using 2nd edition? Absolutely. Fold gold for XP back in, reduce combat XP to compensate, use the 1st edition treasure tables and monster manuals, fix a few rules holes, and draw on the vast OSR/old-school knowledge base for how to run that style of campaign that the 2nd ed DMG fails to give you, and it can be accomplished with little difficulty. The vast majority of 2nd edition's rules changes are matters of taste or mechanical tinkering, not of style, and there's clear improvements (in some places, anyways) in terms of accessibility and overall layout. That it doesn't support an old-school game out of the box doesn't mean it can't be made to support it at all, and if you prefer its layout or enjoy the rules tweaks it made, it makes perfect sense to make some mostly simple changes and run your old-school game with it as you normally would. And as the old-school isn't the be-all and end-all of D&D, you can still get an enjoyable heroic or other style game out of 2nd edition: as I've mentioned previously, this isn't a series intended to delineate right vs. wrong (though I do feel rather strongly that 2nd edition does feel comparatively directionless, not attempting to do something other than "be a fantasy game" with an implied shift to the heroic but next to no rules changes to actually facilitate this).[12]

Even for an old-school player, there's lots of decent material that came out during 2nd edition that is of use. The long-running Monstrous Compendium series offers mountains of additional monsters. The Diablo II: The Awakening supplement and the mammoth Encyclopedia Magica series gives you thousands of magic items to play with, and the four-volume Wizard's Spell Compendium and three-volume Priest's Spell Compendium are similarly authoritative. For more niche play, the Castle Guide is excellent for those interested in the domain game, while Of Ships and the Sea expands the game into the nautical realm. I've always found the three-book Forgotten Realms series on deities—Faiths & Avatars, Powers & Pantheons, and Demihuman Deities—to be far more useful to steal from (even in non-FF campaigns) than the comparatively tepid Deities & Demigods/Legends & Lore, bound as the latter were to real-life pantheons. And there are even some fun adventures in the period: Night Below is remembered by many as offering the solid basis for a lengthy underdark crawl.

Overall, I think 2nd edition could be said to be at once both the last of the old-school

editions and the first of the modern ones. Committing to neither wholeheartedly, it's prone to

being lumped in with—and at the same time disappointing—fans of both playstyles.

What we have in this new edition is a better version than the first one. It is a new version that can provide even more fun and excitement. It is also a smoother flowing game that can work to stimulate the player's own imagination in even more new and exciting ways.

—Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition Preview

I see no need to delve into 3rd edition and later in any deep fashion: I think by this point

it's clear that by 1989 the game had firmly moved away from its

original base in numerous ways large and small: staff, support

materials, rules framework, and general design intent. Insofar as 3rd

edition matters specifically, we'll cover it in the next post, when I

examine the birth of the OSR itself.

[1] Accurate sales figures for TSR are notoriously difficult to come by, and it should be cautioned that there are numerous contradictory figures out there, likely a product of the various lawsuits TSR was involved in that relied on how much money the company was making, as well as the degree to which TSR worked at times to conceal these figures and whether one is looking at core book sales or sales overall. Additionally, it is easy to lose sight of game-related sales amongst the larger sales volume of TSR as a whole, which came to include things like novels. Benjamin Riggs posted some relevant information on Facebook back in 2019, and this Jon Peterson article and his book Game Wizards takes a close look at the matter as well.

[2] The raging arguments over ascending vs descending armour class aside, the observation that, were negative armour class not in use at the game's start, no one would have ever seen the need to invent it, has always struck me as a powerful one. Steve Winter explained that "We heard so many times, ‘Why did you keep armour classes going down instead of going up?’ People somehow thought that that idea had never occurred to us. We had tons of ideas that we would have loved to do, but we still had a fairly narrow mandate that whatever was in print should still be largely compatible with second edition.”

[3] Page 47 (1989 version). "Hero" appears seven times in the 1st edition PHB (mostly with regard to heroism effects from potions), 38 times in the 2nd edition PHB. At the same time, the 1st edition DMG's beginning does speak of populating "imaginary worlds with larger-than-life heroes and villains", so certainly there are hints of such behaviour even there in the 70s.

[4]

Jennell Jaquays also stated that this material was originally intended

for the DMG: see the Grogtalk #86 (21 June 2021) interview, timestamp 3

hours 23 minutes.

[5] Besides the DMGR1 quotes that follow, see also Jonathan Tweet's "Freestyle Campaigning" chapter in DMGR5. Also, I'm not clear on why DMGR1 a) is called the Catacomb Guide rather than the Dungeon Guide, and b) has no catacombs, strangely enough.

[6] Or it was just lost in editing. It's always dangerous to speculate on these things without adequate information.

[7] The DMG did offer a DM the opportunity to declare an area "particularly dangerous", raising the encounter rate to 1 in 10 per turn, which is notably higher than 1 in 6 per 3 turns. However, as the movement rate remains 10 times as fast, even with this change the overall result taken as a dungeon whole results in markedly fewer encounters, since you're clearing a dungeon far faster.

[8] The effect of Charisma is only explained in the PHB, in natural language on the page before the Charisma chart, while the section in the DMG doesn't mention Charisma modifiers at all, strangely. As such, how Charisma modifiers were supposed to interact with the chart was easily missed (as I did for quite a while). Neither Sage Advice, the errata, or the 1995 re-release ever bothered to address the issue, perhaps an indicator as to how few people were bothering with encounter reaction by this point: between the cumbersome implementation and the general incentive to kill things, why would you? However, the Complete Wizard's Handbook (of all books) did contain a clarifier. Regardless, the table is still structurally inclined to aggression as a whole, by having any other positive effect push the result towards a Hostile result.

[9] Though the section at times reads as though two different sections were glued together somewhat haphazardly. Page 45 lists character survival as a primary criteria for XP gain, stating that "Although having a character live from game session to game session is a reward in itself, a player should also receive experience points when his character survives." However, page 47 then deals with survival awards again, stating "Finally, you can award points on the basis of survival. The amount awarded is entirely up to you. However, such awards should be kept small and reserved for truly momentous occasions. Survival is its own reward."

[10] The complete removal of training costs and the domain game in 3rd edition core was a major shift in this direction, though the commodification of magic items in that edition somewhat compensated.

[11] Late 2022 postscript: Melan has a succinct summation of how many old-school fans perceived 2nd edition over at Beyond Fomalhaut:

Old-school gaming came not to praise 2e but to bury it; it quite clearly got established by guys who hated 2e’s guts as much or even more than they did 3e’s. More than this antipathy, old-school gaming is a deliberate rejection of the 2e legacy, a style and school of thought which set itself up as its polar opposite in aesthetics, focus, design principles, and GMing style. Its advocates saw 2e as a corrupted, bland, corporate husk of the original D&D spirit, and thought it was like a swig of clear spring water when they could finally get back to what they saw as the buried genius of those creative origins. This is why it is named old-school after all: from the vantage point of 2022, all TSR D&D might seem old, but for those in the early and mid-2000s, the 2e era was still kind of a fresh wound, and in no way was it considered worth preserving.

[12] Interestingly, "soul" was literally forbidden from 2nd edition TSR products, but I'm sure that's a coincidence.