|

| Dragon #22 - nothing to do with this article |

While it might appear to be a no-brainer, I think an essential—and often overlooked—element of game design is asking the question, "what sort of gameplay does this rule actually create?".

The answer always trumps what the rules text actually says or the intention

behind it, and is why so many apologist arguments based on "but that's

not how it's supposed to be done!" fail to convince despite the empirical truth behind them. When faced again and again with the natural outgrowth of a rule, at a certain point the logical response is to acknowledge that that's the reality, regardless of intention, and either reword the rule to better get what you originally intended, or acknowledge how it's actually being played in the wider environment and reinforce that. I'll be returning to this point throughout the text.

Fanatical game hobbyists often express the opinion that DUNGEONS & DRAGONS will continue as an ever-expanding, always improving game system. TSR and I see it a bit differently. … Americans have somehow come to equate change with improvement. Somehow the school of continuing evolution has conceived that D&D can go on in a state of flux, each new version “new and improved!” From a standpoint of sales, I beam broadly at the very thought of an unending string of new, improved, super, energized, versions of D&D being hyped to the loyal followers of the gaming hobby in general and role playing fantasy games in particular. As a game designer I do not agree, particularly as a gamer who began with chess. … As all of the ADVANCED D&D system is not written yet, it is a bit early for prognostication, but I envision only minor expansions and some rules amending on a gradual, edition to edition, basis. When you have a fine product, it is time to let well enough alone. I do not believe that hobbyists and casual players should be continually barraged with new rules, new systems, and new drains on their purses. Certainly there will be changes, for the game is not perfect; but I do not believe the game is so imperfect as to require constant improvement.

True to this pronouncement, once AD&D’s last core volume—the DMG—was released in August 1979, support for the game focused primarily on adventures, with the occasional other item such as DM shields, monster manuals, geomorphs, official beach towels, and so on. It wasn’t until 1985, when TSR’s dire financial straits combined with Gygax’s accumulated backlog of Dragon magazine articles to produce Unearthed Arcana (UA), that we saw a major new rules supplement. This sourcebook introduced a host of changes, mostly dubious, but while the material within it was perfectly capable of unbalancing campaigns,[1] it was not due to an alteration of the game's central design philosophy but because much of the material was poorly playtested. In other words, most of UA is perfectly old school in tone, just bad.—Gary Gygax, Dragon #22 (February 1979)

The Decline of the Old School — Skill Systems

More relevant for our purposes than UA is the other

hardback rules volume of 1985: Oriental Adventures (OA). Following close on their heels was the 1986

duo of the Dungeoneer’s and Wilderness Survival Guides. Collectively, the effect of the sudden

appearance of these four new rules-laden hardbacks six years after the last official

AD&D rules release, plus the marked drop-off in module quality in 1984 (typically exemplified by Dragonlance) and Dragon’s insistence that all material going forward would

use the UA rules when relevant,[2] eventually led players to refer to this late

period of 1st edition’s life as 1.5 edition (or 1.5e).[3] A major element of this "new" quasi-edition was that the three non-UA books all fielded D&D’s first (non-thief) skill system: the non-weapon

proficiency (NWP) rules.[4]

More relevant for our purposes than UA is the other

hardback rules volume of 1985: Oriental Adventures (OA). Following close on their heels was the 1986

duo of the Dungeoneer’s and Wilderness Survival Guides. Collectively, the effect of the sudden

appearance of these four new rules-laden hardbacks six years after the last official

AD&D rules release, plus the marked drop-off in module quality in 1984 (typically exemplified by Dragonlance) and Dragon’s insistence that all material going forward would

use the UA rules when relevant,[2] eventually led players to refer to this late

period of 1st edition’s life as 1.5 edition (or 1.5e).[3] A major element of this "new" quasi-edition was that the three non-UA books all fielded D&D’s first (non-thief) skill system: the non-weapon

proficiency (NWP) rules.[4] |

| OD&D Vol. III p. 13. Click to enlarge. |

Good or bad effects on play by the concept aside (and there is certainly a school of thought even amongst old-school players that there's nothing wrong with just rolling for searches rather than wasting an enormous amount of playtime pixelbitching your way across a room), this all assumes that the skill system was well constructed. However, in these early days of RPG design, the pitfalls of these systems were easily missed, and mistakes were made. There is a sort of cobra effect present in many skill systems, in that rules designed to increase variety and player options can actually wind up reducing them. Before NWPs, a general principle of D&D might be termed “assume competence”: it was presumed that players could survive in the wilderness, ride a horse, start a fire, and other typical adventuring tasks. Generally, there was a broad swath of everyman knowledge and abilities related to adventuring (the PC realm) and then everything else (alchemy, deep lore, crafting, etc), which tended to be shunted off to the NPC realm.

Of course,

this was just for Oriental Adventures. For non-OA AD&D campaigns, NWPs

came into the ruleset via the Dungeoneer’s and Wilderness

Survival Guides. Each had a variant of

the OA system, with more focus on the environment under consideration; each was

expressly optional. While these books

are generally considered the nadir of 1st edition, to their credit the

designers did correct some of the mistakes of OA. There was a specific statement that "Under normal circumstances, there is no chance of failure involved when characters attempt to use most nonweapon proficiencies". The NWP writeups reflected this. For example, fire-building now allowed one to start a fire

without flint or a tinderbox; if you had these, you started a fire

twice as fast as normal, which is a clear advantage if you actually cared to time firestarting. Boating, Foraging, Mountaineering, Hunting:

all these skills were mostly worded so that you were better than the average person at

these things, rather than being allowed to do them at all. Nonetheless, a wider tendency developed that restricted anything interesting along these lines to holders of the relevant

skill, leaving the everyday adventurer less capable than in pre-skill days.[8] Again, another clash of intent versus actual play appears.

Of course,

this was just for Oriental Adventures. For non-OA AD&D campaigns, NWPs

came into the ruleset via the Dungeoneer’s and Wilderness

Survival Guides. Each had a variant of

the OA system, with more focus on the environment under consideration; each was

expressly optional. While these books

are generally considered the nadir of 1st edition, to their credit the

designers did correct some of the mistakes of OA. There was a specific statement that "Under normal circumstances, there is no chance of failure involved when characters attempt to use most nonweapon proficiencies". The NWP writeups reflected this. For example, fire-building now allowed one to start a fire

without flint or a tinderbox; if you had these, you started a fire

twice as fast as normal, which is a clear advantage if you actually cared to time firestarting. Boating, Foraging, Mountaineering, Hunting:

all these skills were mostly worded so that you were better than the average person at

these things, rather than being allowed to do them at all. Nonetheless, a wider tendency developed that restricted anything interesting along these lines to holders of the relevant

skill, leaving the everyday adventurer less capable than in pre-skill days.[8] Again, another clash of intent versus actual play appears.Outside the realm of the player character, skill systems can also have a major effect on adventure design. When implemented intelligently they increase scenario complexity in entertaining ways, offering varying approaches to key problems. When handled poorly, however, they can literally cripple an adventure. The most common such design error is “roll to play”. If the players don’t make their Etiquette skill check, the key NPC won’t help them; if they fail their Lockpicking roll, the door to the dungeon won’t open. While some might find it hard to believe that anyone would write such a scenario, a quick glance at adventures reviewed at tenfootpole.org makes it clear that this longstanding issue continues today.[10]

Issues or not, the NWP system began seeing implementation outside the new rulebooks. The first ever appearance of skill use in a D&D adventure comes in 1986’s OA1 (Swords of the Daimyo):

In addition to these items, there is a beautifully done sutra scroll in the library worth 500 tael to the Konjo Temple. However, only characters with religion proficiency are able to identify the true value of this scroll.This is also notable in that up to this point, under our “assume competence” mantra, PCs were assumed to be skilled appraisers of all things lootable. Here, however, we have gold (and thus XP) locked away behind a skill wall. It’s only a small and isolated amount, but notable all the same.

D&D’s first ever skill check appeared in a random encounter in 1987’s OA3 (Ochimo the Spirit Warrior):

In terms of non-Oriental Adventures modules, 1987's The Grand Duchy of Karameikos Gazetteer introduced limited skills to BECMI, including D&D’s first proper social skills (Bargaining and Persuasion), while that same year's H3 (The Bloodstone Wars) was the first non-OA module to make the assumption that the group was using proficiencies:These sea spirit folk are intrigued by the Kozakuran ways, in particular such arts as calligraphy, poetry, noh, origami, and tea ceremony. A character proficient in any of these peaceful areas may attempt to impress the sea spirit folk’s daimyo to allow safe passage. Base chance of success is a roll of 11 or less on 1d20, modified by the number of proficiency slots taken in the appropriate area. If a spirit folk PC performs the task, add a +1 bonus to the roll, while a sea spirit folk PC who performs the task gains a +2 bonus. Success indicates that the sea spirit lord is impressed and allows the ship to pass without further incident. The individual who demonstrated the proficiency is awarded 100 XP and a point of honor for his actions. Failure indicates that the sea spirit lord was unimpressed, and the character loses a point of honor.

If no one has any of these peaceful skills (or will not admit to them), the sea spirit folk, sullen and disappointed, grant the ship passage for twice the normal tribute. The next day the ship is becalmed in addition to any other event.

Please note that characters without swimming proficiency should have substantial penalties when fighting submerged.Such an implementation was actually more interesting than the standard approach, which typically would have just applied the substantial penalty to everyone in the water and called it a day.

The Non-Weapon Proficiency system having been pioneered by David Cook, it is no surprise that it became core in 2nd edition, for which he was the lead developer. The skills used there largely follow their form in the Survival Guides (including being based on ability scores). The system as a whole remained optional, like so much content in the system, as Cook saw 2nd edition as a modular ruleset: continuing in the DIY spirit of early D&D, he wanted to permit DMs to assemble their own personal ruleset out of the toolkit the official books provided. Following from this admirable approach, allowances were made for people to continue playing in the old, “make it up as you go” fashion, with some notes on the advantages and disadvantages of such:

The biggest drawback to this method is that there are no rules to resolve tricky situations. The DM must make it up during play. Some players and DMs enjoy doing us. They think up good answers quickly. Many consider this to be a large part of the fun. This method is perfect for them, and they should use it.

Other players and DMs like to have clear rules to prevent arguments. If this is the case for your group, it is better to use secondary skills or nonweapon proficiencies.

But skills as a whole were by this point firmly embedded in RPG culture, and so you would see NWPs steadily employed in official D&D materials going forward (including an optional "General Skills" system in 1991's Rules Cyclopedia, the last major core rulebook for Basic D&D). The extremely popular Complete series embraced them from day one: PHBR1 The Complete Fighter’s Handbook, debuting alongside the 2nd edition core rulebooks, made proficiencies mandatory if you wanted to use its contents, as did 1990's PHBR3 (for priests). PHBR2 The Complete Thief’s Handbook “highly recommended" them. By the close of 2nd edition there were some 150 General NWPs in existence plus dozens more that were setting, class and race specific, including such adventuring stalwarts as Cobbling, Cheesemaking, Flower Arranging, Pest Control, and Pottery.

By the time NWPs (rebadged as skills) were made both core and mandatory for the release of 2000's 3rd edition, they were already a widely accepted part of the D&D landscape. The new edition's more important change was in how it expanded the skill realm. Specifically, 3rd edition introduced the concept of the social skill to mainstream D&D. Other games, such as Champions, had long used skills that helped arbitrate social interactions, but until this point D&D had shied away from such, featuring only a few of these, and only in supplements. Now, however, Bluff, Diplomacy, Gather Information, Innuendo, Intimidate, and Sense Motive became core skills, offering core-gameplay interpretations of how to handle interactions.

Supporters of such implementations argue that, just as there are rules to govern combat and other physical activities rather than roleplaying it all out, so should there be for social elements. Just as a player probably isn't particularly skilled at melee combat but can create a character who is, a player who may be terrible at smooth-talking in real life should be able to play a suave trickster and have the rules back that up, rather than being always condemned to fumbling whenever it's time for negotiation because the DM doesn't think much of their real-life abilities in that regard.

While I can understand that line of thinking, there's no doubt that the overall effect to moving social interaction to the realm of rules does remove a lot of the freewheeling nature of such.[11] It also further shifted gameplay to the button-pushing mode I referenced earlier. Instead of “I approach the guard with a friendly look on my face. I sympathize with him about the cold and the job, then slip him ten silver and ask if he’ll let us pass”, you tend to get “I use Diplomacy to bribe the guard”. It's easy to sympathize with the designers, who likely never intended for this to happen, but at this point we once again go back to the game design question I opened this post with. "What sort of gameplay does this rule actually create?". The answer always trumps what the text actually says or the intention behind it, and in this case, I think the result at the table is clear, based on the many, many complaints this aspect of 3rd edition has generated over the years.

Third edition also had some rather awful implementations of specific social skills. While it was smart enough to make them untrained skills (meaning that anyone could attempt them, skill or no), Sense Motive in particular was obnoxious. "Use this skill to tell when someone is bluffing you. ... A successful check allows you to avoid being bluffed.... You can also use the skill to tell when something is up (something odd is going on that you were unaware of) or to assess someone’s trustworthiness." In actual play, this very quickly became Detect Lie. There was also a "hunch" aspect to the skill that theoretically allowed a DM to convey imperfect information ("You can get the feeling from another’s behavior that something is wrong, such as when you’re talking to an imposter. Alternatively, you can get the feeling that someone is trustworthy"), but in practice it was merely a slightly vaguer lie detector: while the DM didn't have to tell the player that their check succeeded, there was not really any grounds for giving false hunches as the result of successful checks, so "you get the feeling that he's lying to you" was usually just a longwinded way of the DM saying "he's lying to you". The skill even let you detect if someone was under the influence of enchantment magic.

Third edition also had some rather awful implementations of specific social skills. While it was smart enough to make them untrained skills (meaning that anyone could attempt them, skill or no), Sense Motive in particular was obnoxious. "Use this skill to tell when someone is bluffing you. ... A successful check allows you to avoid being bluffed.... You can also use the skill to tell when something is up (something odd is going on that you were unaware of) or to assess someone’s trustworthiness." In actual play, this very quickly became Detect Lie. There was also a "hunch" aspect to the skill that theoretically allowed a DM to convey imperfect information ("You can get the feeling from another’s behavior that something is wrong, such as when you’re talking to an imposter. Alternatively, you can get the feeling that someone is trustworthy"), but in practice it was merely a slightly vaguer lie detector: while the DM didn't have to tell the player that their check succeeded, there was not really any grounds for giving false hunches as the result of successful checks, so "you get the feeling that he's lying to you" was usually just a longwinded way of the DM saying "he's lying to you". The skill even let you detect if someone was under the influence of enchantment magic.While not social, 3rd edition's skill list also introduced the notorious Search skill, which governed finding secret doors and traps. By this point I think the central complaint about such a concept from an old-school perspective is clear (interrogative play vs. roll to solve the problem), and so there's no need to belabour the point.

The Decline of the Old School — Universal Task Resolution

One of D&D's few outright design failures is in its attitude towards ability scores: that it has always warred between having attributes randomly determined in some fashion and the vital importance of attributes in general.

It was not always this way. OD&D core (1974) placed very little value on attributes. No class or race required a set score minimum to play. Only Charisma, Constitution, and Dexterity had any class-independent mechanical effects at all, and these were weak compared to modern effects, as you can see.

|

| Ability score effects in OD&D |

The other scores only mattered in terms of determining bonus or negative XP earned, if one of them happened to be the prime requisite for your class: you could gain up to 10% bonus XP, for example, if you were a Magic User and had an Intelligence of 15+, or lose up to 20% of all earned XP if your prime requisite was 6 or less. Otherwise Intelligence didn't officially matter one way or the other.

With such comparatively weak effects, what would become the old-school standard of 3D6 to determine attributes worked fine, and there was nothing unusual or especially difficult about playing a character with average or even low ability scores. From the release of Supplement I: Greyhawk (1975) onward, however, attributes starting granting higher bonuses to more things and being required to access more of the available classes. In Greyhawk, Strength and Intelligence received non-class dependent effects, to match Dex, Con and Charisma, while the effects of Constitution were increased. The supplement was also the first to introduce demihuman level limits based on their attributes. For example, Elves, originally limited to 4th level as Fighters, could now become 5th level if they had Strength 17, and 6th level with an 18.

It's not necessary to detail every change in the old-school rules that increased the importance of ability scores: it's enough to understand that ability score creep started early, culminating in AD&D. This led to increasingly convoluted rolling

methods to “randomly” generate scores while still ensuring high enough values were

generated to keep players happy, Unearthed Arcana's infamous Method V being the best example.[12]

But while the above illustrates the steadily increasing importance of ability scores, this only shows how the design intent behind the game shifted in its first decade. To some degree this sort of progression was natural: if you're going to bother having ability scores, they might as well actually do something in game terms, after all. Other than inviting stat inflation and an encouragement to cheat during character creation, this evolution didn't really change the fabric of old-school play much. Where this matters is more in what this set the stage for.

The ability score check, where one tries to roll equal to or under their ability score to succeed at something, was first seen in

proto-form in Dragon #1 (1976), in an incredibly convoluted fan article that was

promptly ignored forever. In official

terms, the AD&D spells Dig and Phantasmal Killer were the only core points of that ruleset to employ such a mechanic, in one-off fashions: the core manner of resolution for any given task was "figure out if it involved an element of chance, and if so, figure out some odds for it on the spot, applying modifiers as the DM deemed necessary." Of course, officially this is pretty much the way most every RPG is handled. The key difference is that most games come with a standard method by which this is done: a core mechanic that handles such situations. As per the opening of this article, for old-school D&D, there was none. If it wasn't specifically covered by the rules, you made it up how to resolve it entirely, including the roll (if any) or other resolution method involved in resolving it. Lest we get too revisionist, rolls still occurred all the time to resolve matters: every DM formed basic assumptions or principles to guide their decision-making process, and this often defaulted to the dice (as suggested by the DMG, p. 110). The importance here is not in some sort of idea of dice versus no dice, but in the fact that there was no assumption in the rules that dice were required for such resolutions, let alone that everything could or should be resolved that way and that there was further a pre-defined, "proper" way to do so. This may sound like splitting hairs, but the actual effects in terms of gameplay are enormous.

|

| Moldvay Basic, 1981 |

Ability score checks are simple, intuitive, and quick: it's no surprise that from such ad-hoc beginnings they grew to become the favoured task resolution method of many groups and then systems. Third edition made ability checks an unambiguous core rule: anything that was not resolved via skills (which were modified by attributes) was to be handled via ability checks. Their elegance conceals several dangers, however. For one, as written above concerning the Survival Guide ability score-based proficiency system, there's little granularity to such checks unless you are very free with modifiers: players with high stats almost always succeed, and players without very often or almost always fail. Secondly, everything written above about the button-pushing tendency created by skills applies twice as much to the ability score check: whereas a skill is by its very nature bounded to a specific area, even if a broadly applicable one like "Search", the ability score check marks the arrival to D&D of universal task resolution. Anything could, and eventually was officially required to be, adjudicated using it. Rather than challenges being solved via the interplay between player and DM, ruled on an ad-hoc basis, the first few rolls a player made during character creation determined much of their success rate at almost any given activity in all the weeks or months of play ahead, and the dice were first and foremost the means by which you mechanically interacted with the world--and now there was a mechanical interaction for almost everything. The entire core resolution methodology of the game became, in some fashion, button pushing.

Again, while one can argue that the negative gameplay results of such were not intended and are by no means completely necessary, the obvious differences between the play style of old-school D&D versus third edition and later are, I'd argue, no coincidence. Though the official ability score generation rule for AD&D and its successors largely remained Method I from edition to edition (excepting 2nd and 4th ed, though even in 4th it was one of three available methods), ever-escalating ability scores became the norm, until the very idea of playing with scores that applied negative modifiers was often seen as ridiculous. More importantly, a clean, fair, consistent, easy to use system wound up smoothing away a kludgy,

improvised, inconsistent, occasionally abused, and extremely interesting fundamental

element of the old-school playstyle, and the result was that the emphasis on player creativity over what was

on one's character sheet swung decidedly the other way.

I am writing in opposition to all of these new nonweapon proficiency rules. They are boring, damaging to campaign balance, and simply don’t belong in AD&D games. They are boring in that they slow down play and give players a whole new set of statistics to worry about. They damage balance in cases such as when a fair-size party covers almost all of the best proficiencies; situations that normally require thought and problem solving are easily taken care of. For example, in the AD&D module WG4 The Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun, there is a scene in which the PCs are forced to either have a desperate battle in the dark or hold off a demon until they can find the secret of lighting the area. Thanks to proficiencies, the local barbarian could blind-fight the thing to death, and the party could figure out the lighting at its leisure. If you want proficiencies, there are plenty of games out there loaded with proficiencies; play them. The AD&D game is one of DM’s judgment and improvising.

—Bahman Rabii, Dragon #137 (September 1988)

Next time I'll be focusing on the broader changes introduced by 2nd edition, to explore how that edition is commonly charged both with being too similar and too different to what had come before.

[1] See, for just one example, Len Lakofka’s article analyzing the new weapon specialization rules: “Specialization and Game Balance”, Dragon #104 (Dec 1985).

[2] “The Transition Starts Now”, Dragon #99 (July 1985).

[3] The first reference to 1.5e I can find is from 1995, in the rec.games.frp.dnd usenet group.

[4] I'm not including the 1st edition DMG's Secondary Skill system here. This system, which gave a character a pre-adventuring career (e.g. farming, sailor, teamster, hunter, trapper), and a broad knowledge base derived from this, featured no rolls or special abilities. It was "up to the DM to create and/or adjudicate situations in which these skills are used or useful to the player character." This system would be featured as an option in 2nd edition as well, alongside the NWP system.

[5] The common OSR approach to secret doors, as epitomized in Matt Finch's influential A Quick Primer, largely follows the AD&D and earlier approach, but as we have seen, it was not the only method used in old-school play and there has been some pushback against Finch's depiction as overly reductive or even anachronistic. See this Alexandrian article for a 2009 example of such.

[6] Another good example of such

includes the D&D/AD&D thief, whose skill-based set of abilities

lent itself well to button-based gameplay ("I search for traps"—*rolls*). See also this article on "hidden skills" in B/X, and Grognardia's overview of the thief's role in D&D. At the same time, for those who find

the traditional OSR interrogative approach to be an exercise in pixelbitching, cutting

to the chase with a simple mechanical solution can be very freeing. Similarly, placing the burden of estimating

risk vs reward and the mechanical execution thereof on DMs relied on the DM

being good at doing that on the fly, and many were not, easily leading to

frustrated players and relief at having something codified by professionals

(though one look at the procedures in the Survival Guides made it clear that

professionals did not always get it right).

Again, we’re largely speaking of how approaches can differ and change,

rather than always contrasting right vs. wrong.

[7] Looking back on nonweapon proficiencies in 2008, in a thread on Dragonsfoot Cook wrote, "I think they were a good thing. One of the things dreadfully lacking from AD&D was any sense that your character had a real life beyond class skills. This gave players a way to create a more culturally informed background for their character. Well-used and applied, proficiencies were a way to say things like "This is the result of being raised by farmers/wolves/priests/pirates." It got people to think about their characters as something other than being sprung fully formed from the forehead of Zeus. Now proficiencies didn't work as well when they just became excuses to do special things in combat. At that point they lost the sense of making your character more than a class and became another way to munchkinize him."

[8] As an example, the very first non-OA skill check in D&D—1988's I14 (Swords of the Iron Legion)—appears in a scene where a horse breaks free and runs wild in the streets. Unless someone has Speak with Animals, only a character with Animal Handling is permitted to deal with it in a fashion besides just killing it.

[9] 3D6 down the line was used in OD&D, Holmes, B/X, BECMI, and AD&D 2nd edition; 1st edition was the outlier in this regard. Note that several of these had "hopeless character" clauses that allowed you to discard PCs who had very low scores. I think the popularity of 3D6 down the line in the OSR is one-part the dominance of B/X over AD&D and one part "hardercore than thou" zeal of the converted exhibited by some of the OSR's adherents.

[10] Another issue is the quantum skill check, where a skill check result is delivered regardless of player actions. For example, “If the party fails the check, an NPC just points the fact out.” In these cases, pass or fail: the result is the same. This however just tends to signal a certain pedestrian strain of design rather than actually ruining the adventure.

[11] I also find interesting 2nd edition dev Steve Winter's notion that "The counter argument, which I seldom hear, is that relying on a numerical system to resolve skill use rewards players who are good number maximizers at the expense of those who are not. By favoring one approach over the other, aren't we just swapping one type of player talent for another?"

[12] For a statistical analysis of the standard old-school ability score rolling methods, see this Dragonsfoot thread. Note that its Summary 3 has a couple of minor errors. For a magic-user using Method 0, the chance is 70.64%, not 74.07%, and for an illusionist using Method 0, the chance is 0.43%, not 1.50%. Additionally, I think all the Method 3 values are wrong, not that anyone generally uses that method.

[13] According to Daniel Boggs over at Hidden in Shadows, Arneson employed a version of attribute checks in the 70s, though as with so much related to Arneson the details are a bit vague.

PC skills were introduced to BECMI via the Gazetteers, starting with Gaz 1 "The Grand Duchy of Karameikos" (1987). Every new gazetteer introduced a few more subsetting-specific skills, if I remember correctly, and these were then collected and incorporated into the Rules Cyclopedia, when it came out.

ReplyDeleteI distinctly remember the shift to using skills when we started using the gazetteers. Thankfully, we were already steeped in old school play, and so largely ignored them after the players added them to their character sheets.

I updated the post to mention GAZ1 rather than GAZ5. Thanks!

Delete> "compare the common interrogative method of a tailored exploration of your surroundings in old-school play with “I make a Search check”.[5]"

ReplyDeleteI'd take issue with the assertion that the "push button" search is a new school thing. From the start of D&D and as laid out very clearly in the play examples in the darling of the OSR, B/X, the rules-as-written way to handle traps and secret doors is a push-button 1-in-6 (for most classes) rolled Search of a 10'x10' area.

I personally Referee a mix of the OSR descriptive search and the B/X push-button Search, and I do see considerable value in the former, but I think it's somewhat revisionist to claim that said descriptive search is actually an "old-school" thing without actual evidence that's how people played it back then - and even if that's how people played it back then it's going beyond the rules, not the gameplay the rules promote.

The example of play in the 1st edition DMG very much goes into narrative description of the search for a secret door (see p. 99), which matches with interviews I've read. That having been said, I should probably call all that out rather than just implying, and the existing buttons in the original rulesets should be better mentioned, so I'll make some edits above. Thanks.

Delete(I also use a mix: I environments that have either too much detail or too little detail are poorly served with the narrative method).

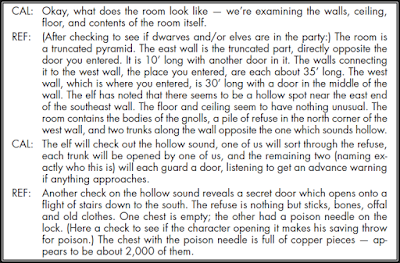

FWIW, there are a couple of examples of players searching in OD&D in U&WA p13. The players give brief statements of where they are looking, then the ref tells what they find. it's unclear from the text whether dice are rolled or not.

ReplyDeleteGood point. I've edited in a reference and shot of the page as an example. Thanks!

DeleteWRT the social skills, OD&D has a 2d6 "reaction" roll to be used when luring monsters--all non-players--into service and generally negotiating with "intelligent monsters" during play. These rolls were modified by the PC's charisma score, but also by player actions such as bribes, threats, etc.

ReplyDeleteI always saw this as a social element, but not really a social skill per se, if that makes sense. By being something that happens whenever applicable, regardless of character choice or stats, it always seemed to me to be more of a base mechanic of the game's encounter system rather than something I'd call a skill. However, as far as I know the OD&D version isn't modified by Charisma, even if using Greyhawk. Reaction was also less applicable in OD&D, at least as far as I understood it, as it only applied to "the more intelligent" monsters and even then, based on the Avoiding Monsters section, only if you were part of an "obviously superior force" (because otherwise they auto-attacked).

DeleteI agree it's not really a "skill" per se; but it's what OD&D has for social interaction instead. FWIW, M&M p11 has: "charisma will aid a character in attracting various monsters to his service" and then p12 has "the monster will react, with appropriate pluses or minuses ... rolling two six-sided dice and adjusting for charisma".

DeleteI have to admit I've never been clear on how these two aspects interact: you get auto-attacking monsters in almost all cases, but the game assumes you can hire some as well. I get that technically you can hire a bunch of goons and then, with your outnumbering the monster cancelling out their auto-attack tendency, proceed to negotiations for hiring, but that seems rather odd as procedures go. Perhaps I'm missing a Strategic Review clarification somewhere, or maybe it's just one more of those enjoyable OD&D oddities/vaguaries where you fill in the blanks as you will. The DM might just decide to designate some critters as open to hiring and ignore the general auto-attack rule, ruling on the fly as they desire.

DeleteI don't recall any thread exploring this in the past. If you have anything I'd be interested in reading it.

I find all the ranting against the ur-devil of "skill systems" pathetic to this day. Is it really the epitome of imagination and creativity to describe how would I climb a tree? Or pick a pocket? "Well, a I probably start with the lower branches and go higher from there" or "I sneak up to the target and try to snatch the loot unnoticed". Whoa, mind fucking blown.

ReplyDeleteIn most old school play, you wouldn't require a roll or a description for a PC to climb a tree. They player would say "my character climbs the treeline unless there is some reason that should have a chance of failure, the character climbs the tree with no fuss. The pickpocket could be resolved with a simple die roll with the odds determined by the GM and discussed with the player before the attempt is made or using the thief skills if they PC is a thief.

ReplyDeleteOkay, but why all the whining about the big bad creativity-stifling skill systems? Saying "I climb a tree" is so amazingly creative?

DeleteBut what is so creative about "I roll a Climb check"?

DeleteThe situation could be handled like this....

DeleteThe DM describes a situation that sounds like it will need training in religious etiquette to resolve.

The players discuss how to resolve the issue and one player states, "My character was raised by his uncle. His uncle had saved a local bishop from a robbery and ambush. The bishop felt indebted to the uncle and committed to paying him back. Years later, the bishop would repay the debt by training the player character in finer language, etiquette, religious protocol, etc.

The DM determines that the character can resolve the situation due to his background and tells the player to write down a few notes on their character sheet so they can be referenced in later play situations.

That's not a greatly detailed example BUT that is more creative than saying, "I roll for x".

IF the DM allows that oh-so-convenient background piece pulled out of your hat on the spot (and if it isn't in contradiction with anything you made up so far), and besides, aren't flashback scenes like that the territory of drama queen hipster STORY GAMER leftist furries, the scum a self-respecting OSR nerd wouldn't even spit on?

ReplyDeleteThe condescending tone I hear again and again, referring to poor stupid "skill rollers" is laughable. I played plenty of games with skill systems where we still had to come up with solutions of our own devising to practical problems, and I had my share of purebred OSR stuff where the epitome of jaw-dropping ideas was "so I pick at the stone slabs with my ten foot pole" for the zillionth time. Might as well just roll and be done with it, thanks.

Wow! I'm not a story gamer or a leftist by any stretch of the imagination. I wasn't responding in a condescending manner at all. I just illustrated one possible way of handling the situation. The DM could have listened to the reasoning and asked for a 75% roll, a 4 out of 6 result, or whatever else would satisfy the situation. I don't think anyone is a "poor stupid skill roller" - YOUR WORDS, not mine - for using skill systems. Some games handle them really well. I'm just saying that allowing the characters a chance to explain something like that fits several genres. How many times has a comic book character brought up something from their past that allowed them a greater than normal chance out of the blue? I believe there is a place for both in games. There's plenty of times where a skill roll will suffice and there's plenty of times when a skill roll can be completely ignored; should someone with the cooking skill be required to roll for a grilled cheese sandwich? I haven't heard any condescending tones in this discussion. I have heard plenty of "don't be a slave to the system" type of examples. I guess I don't understand the vitriol and name calling. Drama Queen, Story Gamer, leftist? None of the above.

DeleteSite your source for "assumed competence".

ReplyDeleteCite your source for Basket-Weaving and Cheesemaking. Pardon the "site" misspelling above.

ReplyDeleteGreat series of articles, but in the interest of historical accuracy: The "skill" system in Bunnies & Burrows was more like D&D's bending bars, learning spells and thieving than the classless paradigm popularized by RuneQuest. The latter has a precedent in Empire of the Petal Throne, however. Published by TSR in 1975 - a year before Bunnies & Burrows - that game used percentile-based skills only loosely connected to character professions. These may have been present in the version self-published by the author, Muhammad Barker, in 1974. Either way, Empire of the Petal Throne deserves credit/blame for introducing classless skills to the hobby.

ReplyDeleteThis is a spectacular article.

ReplyDeleteI am reading the 2e City of Greyhawk boxed set from 1989 and it mentions making bluff checks to trick the guards at the main gate. The guards are so meticulous there that a character attempting such a check has their WIS score multiplied by 4. This style of play had been happening for a long time, people knew it made sense, 3e just finally admitted it and did a good job at codifying the way people had been using the rules in their home games.

ReplyDelete