|

| Sigh. |

Over the course of four parts (I, II, III, IV) of a series nominally about the Old-School Renaissance, we've spent three of them on TSR-era Dungeons & Dragons and one on clones of TSR-era Dungeons & Dragons. I hope by now the reason is clear: rather than a nebulous interest in "old games" (with even what "old" meant being undefined), the OSR was a movement entirely rooted in a specific style of early D&D and cannot be understood without reference to the game that birthed it. This isn't an approach rooted in elitism or exclusion, as is so often charged, but simply an acknowledgement of what actually happened.

This final part is dedicated to explaining how this very concrete base fragmented into the increasingly incoherent movement we see

today, a movement frequently having nothing to do with or even in direct contradiction of what it began as. I want to emphasize that this isn't necessarily about the OSR getting better or worse (although I firmly believe that strong design principles trump vagueness every time), but about how it changed.

I've worked on this part the longest because, having moved away from the concrete realms of official product (corporate and otherwise) and into the realm of ideas, it became harder to document everything thoroughly. As one of the major topics of this part is the decentralization of the OSR, that naturally meant ranging farther and wider in search of material, much of which has vanished due to link rot. It also became more difficult to capture every point of view, as more and more of them developed. Ultimately I can only hope to annoy everyone with my portrayals, thus demonstrating my clear bias in favour of / against all concerned.

The Shape of the OSR Today

I think it's fair to say that there is no singular OSR today: hence all the confusion. However, though people then and now have tortured the issue to arrive at a definition that just so happened to include all their favourite D&D editions and clones while excluding anything they didn't like, what the OSR was is easy to define: it was simply a rebirth of interest in old-school Dungeons & Dragons, specifically as its original designers intended it to be played.[1] Its adherents had never entirely disappeared, but it was certainly a playerbase on life support for the longest time. Around 2007 began a renaissance, one that manifested in a variety of ways but at its heart was firmly rooted in mechanical compatibility with TSR-era D&D and a sharing of certain key design principles that went with those editions and the way their designers intended them to be played (which I hope the earlier entries in this series have clearly laid out).

Before I start the history, I need to lay out where we are now for it to make sense. Today, we have four core groups that different people place under the OSR umbrella:

- Classic OSR: The original wave. Has both compatibility and principles.

- OSR-Adjacent: Some principles, some compatibility.

- NSR[2]: Principles, but not compatibility.

- Commercial OSR: Compatibility, but not principles.

Classic OSR is straightforward: it's what we've been talking about up until now. These are the greybeards that never stopped playing old-school D&D--as well as those that came along later and adopted it as their game of choice while most everyone else had moved on to other editions or games--who decided to work to bring about fresh support for their beloved editions. These players were inspired by the rules of old-school D&D, the principles that run alongside those rules, and the unique gameplay experience that results when you have both working side by side. Classic OSR includes the original old-school TSR editions: the original goal of the OSR was to provide additional content for old-school D&D, after all, rather than to design new games. However, it also includes 21st century games built with the intent of capturing both the compatibility and principles elements, though this can still lead to a great deal of variance. Beyond the classic four I covered in the previous part of this series, this would include games such as LotFP, AS&SH, ACKS, Seven Voyages of Zylarthen, Beyond the Wall, Blueholme, Blood & Treasure, Blood & Bronze, Crypts & Things, Fantastic Heroes & Witchery, Iron Falcon, Greyharp, Delving Deeper, Dark Dungeons, Old-School Essentials, and so on.

These games are often labelled as "retroclones", following on from the original four such games detailed in Part IV, even though (confusingly) many of them are not trying to emulate any specific system. But they unquestionably use D&D rules for the vast majority of their mechanics, and can run a TSR-era module with minimal effort. Their overall experience may emphasize or de-emphasize certain aspects of the old-school D&D experience (e.g. Crypts & Things and its focus on the sword & sorcery element of D&D DNA, LotFP with its emphasis on horror and late Renaissance/early Enlightenment elements), but the broad feel and gameplay will still be D&D, albeit stretched sometimes as far as it can go (and perhaps beyond that, depending on who you talk to).

|

| Daniel Proctor (creator of Labyrinth Lord), June 2011 |

OSR-Adjacent games are those that like some of the trappings of old-school D&D but don't really want to commit to it all the way. The principles they embrace are not entirely consistent, but usually include one or more of resource tracking, higher lethality, the vague "feel" of the old-school, and an emphasis on the dungeon as setting. DCC, with its third-edition framework, new stats and dice and spell list all breaking compatibility and its lack of several key old-school rules (no basic resource tracking or gold for XP) is a good example (it aims for feel, lethality, and the dungeon as frequent setting). Rules-light, not really an accurate OSR principle but regularly assumed to be one (more on that below), is often embraced by these games. This category also includes games that bolt modern narrative gaming elements onto an essentially D&D core, but perhaps the most numerous examples of this subgroup are the various attempts to make a later edition of D&D into more of an old-school game: Fourthcore, 5e Hardcore Mode, Dungeonesque, Five Torches Deep, Into the Unknown, Olde Swords Reign, and so on (resource tracking, lethality, the dungeon as frequent setting). Also included are the "hacks", those ultra-stripped-down games that remove almost everything in order to be as minimalist as possible: good examples include many of the various Microlite series of games (74, 75, 78, 81), Swords & Wizardry Light, HERE'S SOME FUCKING D&D (no, really), Searchers of the Unknown, and then newer takes like Knave, The Black Hack, and Bluehack.[3]

From a strictly mechanical perspective, all OSR-Adjacent games can be used to run old-school/OSR modules. However, much more conversion work than usual is typically required, and going the other way--attempting to use old-school/OSR rules to run modules made expressly for these systems (such as DCC or 5th ed modules)--takes yet more work again. For example, Knave has no bestiary or magic item list and uses a custom spell list, meaning that any time you encounter a typical D&D monster, spell, or magic item you need to haul out a separate D&D book to learn what it does. From a principles standpoint, these games (especially the hacks) also tend to jettison large amounts of the text that teach you the core gameplay loop of old-school D&D and the principles surrounding it, leading to a poor understanding of what they're derived from and are attempting to do.[4]

The right wing of the OSR tends to congregate with the above two groups, with the exception of the newer "hacks" like Knave.

NSR (New School Revolution) games are those who feel that there are valuable principles to be learned from old-school D&D, or that the general conceptual framework of old-school dungeoneering is interesting, but that the specific rules of old-school D&D are not needed. In other words, you can't play D&D with these games (at least, not without a ton of conversion work). The principles these systems espouse usually encompass rules-light (non-D&D) frameworks and an emphasis on player agency. Games that fall under this rubric would be Sharp Swords & Sinister Spells, Into The Odd, Electric Bastionland, Ultraviolet Grasslands, Troika, Cairn, and Mörk Borg. I also place Dungeon World and Torchbearer in this group (although more as godparents; see below). The left wing of the OSR tends to congregate here.

Commercial OSR is the realm of the grifters and the lazy; when I say that this branch has no principles I mean more than just gameplay. This is not a community or a coherent set of games, but simply a grouping I use to lump in everyone who adds an OSR search tag on their shitty shovelware on DriveThruRPG. They are products, often originally 5th edition in nature, that are or can be converted to old-school D&D with some minimum effort and so are advertised as OSR, but have absolutely nothing old-school about them besides the D&D mechanical base and some kind of (usually generic) fantasy setting. You can usually see a few of these a month being reviewed on tenfootpole, and the unifying theme is how much writers of these products simply Do. Not. Get. It. Rather than rulesets, the Commercial OSR is almost entirely rooted in modules. These have minimal treasure for proper gold-for-XP games, lots of setpiece and often carefully balanced combat encounters a la 5th edition, oceans of read-aloud text dictating player actions, and minimal player agency in general, but might be set in a dungeon or have orcs or something and so the designer slaps an OSR tag on it in the hopes of higher sales.

Not included anywhere above is a vague "old games" category. Some with no grounding in the history of the OSR have become fixated on the "old-school" part of the OSR label and, taking "old-school" to mean only "older than I am" have begun applying to any suitably (arbitrarily) old RPG. As such, you get games like Traveller and Gamma World and RuneQuest and Champions and WEG Star Wars slotted here. Some people now ask if 3rd edition D&D is included, seeing as it's over two decades old at this point. I think any serious reflection would make a person realize that a so-called movement that can encompass D&D, Bunnies & Burrows, Traveller, and Teenagers From Outer Space is conceptually useless except in the broadest categorizational sense (i.e. "RPGs"), but as this confusion occurs all the same I felt it worth covering.

While I think the above is useful in differentiating the various rather different strains of thought that comprise the OSR movement today, the question is, well, how did we get here?

And The Days Go By

By mid-2008 the big four initial retroclones had been released: BFRPG, OSRIC, Labyrinth Lord, and Swords & Wizardry. By this point you were already hearing grumbles that there were too many clones, which seems hilarious considering the avalanche of such that rapidly followed. In this early period of the OSR, designers set down two initial paths.

- True retroclones. Editions that had not yet been tackled were cloned. Examples include White Box (OD&D, 2009), Dark Dungeons (Rules Cyclopedia, 2010), 27th Edition Platemail (Chainmail, 2011), Mazes & Perils and Wizards, Warriors & Wyrms (Holmes, 2011), Delving Deeper (OD&D, 2012), and For Gold & Glory (2nd edition AD&D, 2012). Later efforts along the same lines were Blueholme (Holmes, 2013), Iron Falcon (OD&D, 2015), and eventually B/X Essentials (2017) and Old-School Essentials (2019).

- D&D Mods. Games built off of an unabashedly D&D framework, but not seeking to strictly emulate an existing edition. As mentioned above, these games were (and still are) typically lumped in with retroclones, I think because they were being discussed and sometimes developed on the same forums that the initial clones debuted on, and also because some (but not all) began with a core exclusively from one old-school edition, being "X Edition +" in concept. Lamentations of the Flame Princess (2010) would be the biggest and best-known such example (built off of a B/X framework), as well as one of the earliest, but the rest of the long list found above under "Classic OSR" applies here.

Once it was realized that anyone with MS Word could and would take the OGL and release their own preferred D&D-plus-houserules, games came (and went) with regularity and people simply expanded the definition of the OSR to include this phenomenon. Some were happy at the increased choice, others annoyed at the idea that people would try to improve on what already worked fine. The earliest grumbles as to how the OSR related to old-school D&D were over the proliferation of and increased focus on retroclones and what such games meant in terms of the future of the old-school D&D movement.

|

| Click to enlarge. Note "Old-School Renaissance" in quotation marks: the term was in regular use from 2008 onwards, but was still new enough that many still felt it needed to be singled out somehow ("so-called" was another popular adder). Various other proposed labels cropped up, but none took hold. Original thread found here. See also this thread and this thread. |

Few systems beyond the initial four developed much of a userbase: getting there first was the key determinant of success, at least initially. But the focus on rulesets as a whole is quite notable in that this switched the primary creative emphasis from support product (adventures and the like) for D&D--the original intent of the OSR--to creating and supporting related but still separate rules systems.

While this was significant, the truly major fragmentations came in three forms: the evolution of social media, changing product styles, and general commercialization.

Social Media

As seen in part IV, the OSR began as a forum-based movement, Dragonsfoot, K&K and ODD74 being key, with a few other smaller forums playing subsidiary roles. But by 2007 Blogger had picked up steam and was increasingly being used to host important original content. In terms of pivotal early blogs connected to the OSR, we have:

- Jeff's Gameblog (July 2004)

- The Alexandrian (July 2005)

- Trollsmyth (May 2006)

- How to Start a Revolution in 21 Days or Less (August 2006)

- d4 Caltrops (January 2007)

- Delta's D&D Hotspot (March 2007)

- Sham's Grog & Blog (February 2008)

- Grognardia (March 2008)

- The Society of Torch, Rope and Pole (March 2008)

- Greyhawk Grognard (May 2008)

- Lamentations of the Flame Princess (May 2008)

- Monsters and Manuals (May 2008)

- ChicagoWiz's RPG Blog (June 2008)

- Tenkar's Tavern (June 2008)

- The Hydra's Grotto (August 2008)

- Bat in the Attic (October 2008)

- Uhluht’c Awakens (October 2008)

- Cyclopeatron (December 2008)

- Ode to Black Dougal (February 2009)

- Beyond the Black Gate (March 2009)

- Dungeons and Digressions (March 2009)

- Dyson's Dodecahedron (March 2009)

- The Hill Cantons (March 2009)

- Lord of the Green Dragons (March 2009)

- Gothridge Manor (April 2009)

- Wondrous Imaginings (April 2009)

- Telecanter's Receding Rules (May 2009)

- Akratic Wizardry (June 2009)

- B/X Blackrazor (June 2009)

- The Underdark Gazette (October 2009)

- The Mule Abides (October 2009)

- Playing D&D With Porn Stars (October 2009)

The above list of 32 early blogs is by no means exhaustive, and not every one of them started out as OSR blogs (formally or informally) or concerned themselves with just that topic, but I think it covers all the major movers and shakers in this formative period (even if some of them took a little while to get going). You can see by the dates that 2008, the close of the initial burst of the OSR (which I'm placing as the release of Swords & Wizardry in June 2008) coincides with the birth of a lot of these blogs. The effect was that a lot of the key posts--analysis, theory, content--once the OSR took off increasingly began to be made in areas outside the OSR's forum birthplaces. And of course, further notable blogs came along as the movement grew: Hack and Slash (August 2010), Dreams in the Lich House (December 2010), Mythmere's/Uncle Matt's Blog (March 2011), Hall of the Mountain King (April 2011), Hidden in Shadows (July 2011), False Machine (August 2011), Dungeon of Signs (May 2012), etc. But I'm not going to try and list every OSR-related blog that has ever mattered; I think the point is made.[5] While many of the more interesting blog posts were regularly discussed on the forums and many of their creators were also forum members, all the same the movement began to decentralize, as the discussion spaces began to multiply.

Lest I give an impression of too much consensus amongst Classic OSR fans, this outward expansion also had an effect on the core in terms of definitions and muddle. Posters at Dragonsfoot and K&K, under the influence of the wider movement and its rapidly expanding scope, tried to keep up with and hash out what the OSR really was themselves, with some looking to keep the old boundaries, others responding to what was actually happening on the ground and trying to reflect that, and still others trying to do both by introducing a new separation between old-school (actual D&D, nothing else) and whatever the OSR had become. This thread from mid-2010 makes for a good example of the debate.

Following the blog explosion was the launch of Google+ in mid-2011. That ugly social media duckling turned out to be a swan in the eyes of the OSR, as the movement flocked to there early on. To quote the Papers & Pencils blog:

In 2011 the service was launched concurrently with Hangouts, which folks quickly realized was the most powerful game facilitating tool since polyhedral dice. It was only natural that Google+ (which Hangouts was then inextricably connected with) become a tool for finding new people to play and discuss games with. The fact that g+ lacked the social baggage of sites like Facebook, as well as the tools it had for organizing a person’s interactions by topic, gave people a freedom they lacked elsewhere. Nobody’s grandma is on Google+. Nobody had to worry about bothering people by posting too frequently about weird nerd shit. Google’s failure to convince everyone in the world to use the service made it an ideal space for hobbyists who wanted to spend a lot of time talking about something esoteric.

|

| Stuart Robertson's logo, 2011 |

Expanding Horizons

The majority of the OSR's creative energies initially were funnelled into an exploration of D&D proper: new rules like the old days, new dungeons like the old days, new monster manuals like the old days, and so on. Variances were there, but a broad classic D&D European medievalism predominated.

|

| From S3 (Expedition to the Barrier Peaks), 1980 |

But very quickly you had people who weren't content with this. These people were enthused by the rebirth of old-school D&D, but of course that was never just one thing, even (especially) from the earliest days: fantasy/SF mashups, Arnesonian surrealism, high and low fantasy, quests and story versus sandbox site exploration, funhouse dungeoneering, and so on. It's easy to forget today, but Appendix N was a rather diverse list of influences and it took some time for what D&D was "supposed" to encompass and how it was "supposed" to be played to be largely settled on--for it to become that self-referential collection of tropes and genericisms that we now think of whenever we say "D&D".

The overlooked element that enthused the OSR the most was the sword and sorcery aspect of D&D, which as a fantasy fiction phenomenon was rapidly dying out in the late 1970s, just as D&D was getting rolling, and so from a RPG perspective was ripe for a fresh look.[6] It was only natural that people would take the opportunity presented by the birth of the OSR to run with it in more idiosyncratic fashions, either to explore roads usually not taken or, in the case of some creators, to start trails of their own, sometimes with bulldozers. And hand in hand with these creators came players upset that people were going off the reservation. There were always those whose definition of D&D was narrower than others: that didn't include the techno mashup of S3 (Expedition to the Barrier Peaks) or the Looking Glass-whimsy of EX1 and EX2 or what have you, or who might have been happy with all of the above but preferred their murderhobos to be abstract ones rather than knee-deep in vividly-pictured blood and viscera; the morality play implicit in the presence of young monsters throughout B2 was not to everyone's liking. With the OSR explosion, these more conservative players were to come face to face with all sorts of products that claimed to be old-school, representing either minority strands of TSR D&D or things that Gygax would never have cottoned, and the reactions were often strongly negative.

I'm not sure what's going to be more entertaining... the book itself... or the shitstorm that it's going to cause.

—James Raggi, October 2008

In 2008, a longstanding old-school poster by the name of Geoffrey McKinney released Supplement V: Carcosa. Carcosa tossed aside all the typical Tolkienesque elements, replacing this with the sword & sorcery and weird horror of Lovecraft, Howard, Moorcock, Lin Carter, and MAR Barker's The Book of Ebon Bindings. The name itself caused a stir, a seemingly presumptuous insertion of the work into canon alongside the original four OD&D supplements (though, like the selection of booklet sizing over 8.5 x 11, this was merely McKinney attempting a mock historical fidelity). But that was nothing compared to the outrage the contents summoned up, in particular its series of sorcerous rituals.

This one-hour ritual requires the Sorcerer to stand in cold, waist-deep water and to there drown a Jale male baby. He must rend the corpse with his own hands and spill the blood upon a stone

The sacrifice is a virgin White girl eleven years old with long hair. The Sorcerer ... must engage in sexual congress with the sacrifice eleven times, afterwards strangling her with her own hair.

The initial public reception was largely negative (though McKinney reported strong sales). While McKinney's pre-release campaign postings using Carcosa were very well received, creating an eager audience for the book, once it was released its Dragonsfoot review thread became so acrimonious that it was locked, as free speech advocates and people horrified at the thought of child rape in D&D, fictional or not, hammered away at one another.

One reader, however, was quite impressed. James Raggi, an American relocated to Finland, had fixated on horror and the Weird Tales aspect: HP Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, Frank Belknap Long, and the like. This was a traditionally overlooked aspect of D&D, since it wasn't what Gygax was particularly interested in beyond a bit of garnish to his more traditional fantasy tales, and because soon enough Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu came along to explore that niche better than D&D ever could. Raggi ran a successful OSR blog, which made waves early on with his influential 2008 article, I Hate Fun. In May 2008 he decided to make a go at RPG publishing.

|

| An early screenshot of Raggi's publishing venture, Lamentations of the Flame Princess (LotFP). Click to enlarge. |

|

| From the LotFP rulebook |

Raggi also began putting out a large number of his own works. Of the first 14 releases in his LotFP line, 11 are by Raggi. All depart from the traditional dungeoncrawl theme in some major way. For example, Death Frost Doom (LotFP's first adventure) is largely a dungeoncrawl but can easily end in the players unleashing an undead apocalypse upon the world. Tower of the Stargazer, designed to be an introductory adventure, emphasizes the lethality aspect and can be quite punishing to those seeking to fiddle with the environment as is typical for old-school games. Eventually LotFP's modules gained a reputation for unremitting hostility: just as the smartest thing to do in a Call of Cthulhu game is to burn without reading any book you find, the wisest thing to do in a typical early LotFP module is to dynamite the entrance and fuck off to somewhere with only liches and archdemons to worry about. This concept of the dungeon that punishes you for having the temerity to play it became popularly known as the negadungeon, and was strongly associated with LotFP.

The LotFP line was a huge success (at least by indie RPG standards). Taken on their own terms, not every adventure worked, but they were neither generic nor dull. That having been said, not everyone was willing to take them on their own terms: many objected quite strongly to those terms. LotFP adventures soon gained a reputation in the old-school as pretty, bold and different, but also overly stylized examples of excess: shock and horror and trope subversion in a pleasant-looking package, but either unplayable or so unpleasant in tone that they might as well have been. And the fact that these adventures were being gobbled up almost as fast as they could printed and receiving rave reviews by many bloggers led to the beginnings of the first major rift in the old-school community, between those who thought that Carcosa and the LotFP line in general were breaths of fresh air and perfectly acceptable riffs on the old-school D&D formula and those who thought them a bridge too far--in terms of style, content, or both.

DIY D&D & Artpunk

Adding to this was the rise to prominence of Zak Smith, aka Zak S or Zak Sabbath, the blogger behind Playing D&D With Porn Stars and the D&D-based web series I Hit It With My Axe (played with said porn stars). While the title and initial content of his blog (launched October 2009) may have drawn people in, many soon found Zak to be a compelling, insightful writer who threw himself into the OSR, blogging almost daily with his take on it. Smith and Raggi rapidly teamed up, Raggi releasing Smith's work beginning in 2011 with Vornheim, a city-based supplement.

Smith's anarchist leanings, appearance in Maxim, and his own former career in porn combined with a general brash attitude to irritate many old-schoolers, some of whom politically were slightly to the right of Attila the Hun. At the same time, this was not a universal,[8] and while a decent amount of pearl-clutching and think-of-the-children posts occurred on the topic of Zak, many simply claimed that he didn't seem to be playing old-school editions in his broadcasted games and argued that he was a textbook case of style over substance (or just plain found him aggravating, sans politics). When Smith began releasing OSR supplements, such as Vornheim or Alice in Wonderland-themed A Red and Pleasant Land, there was a similar divide between those who saluted him for his vision and those who argued that these products were perhaps pretty,[9] and certainly different, but not especially usable at the table.A 2018 look back by long-time poster T. Foster does a good job in summing up the twinned influence of Raggi and Smith. In reference to a survey asking people what they thought of the OSR, which left out much of anything about the OSR the people who there at the beginning recognized, Foster explained:

|

| Dragonsfoot, Dec 2018. Click to enlarge. |

Smith, an artist, in particular would popularize visual divergences from classic TSR appearances. As Kevin Crawford would point out in 2015 in his "A Brief Study of TSR Book Design", there was a tendency in the OSR to slavishly ape the simple TSR design dress of circa 1981--monocolour covers, Futura or Souvenir fonts, two-column layouts--either to conjure up that old-school feel or just because writers (which OSR people primarily were) are rarely also skilled in art, layout, and graphic design and so graphically took the path of least resistance.[10] Just as Raggi broke with TSR thematically, so too did Smith, but in addition he began to break with the old ways from an aesthetic perspective. His first release, Vornheim, was comparatively conservative in that regard, but he would get bolder as further releases appeared.

| |||

| Veins of the Earth, LotFP, 2017 |

Like Raggi's adventure ideas, Smith's art and layout stylings, part of what he termed "DIY D&D",[11] were controversial with the old guard. Some enjoyed it, or could at least ignore it, but others saw it as ugly, or more substantially an example of style over substance. That the newer generation of OSR enthusiasts was more likely to enjoy this style, and then began to release material of their own aping it in various ways, only encouraged division.[12] Today this style is considered part and parcel of what Patrick Stuart would later term artpunk (a term taken up by Prince of Nothing over at the Age of Dusk blog and now generally associated with him via his No-Artpunk essay and contests). It has created a divide between a group that sees the OSR as stodgy, staid, dogmatic and repetitive, versus those that see artpunks as so focused on visual presentation and challenging conventions that they forget that it's all for a game intended to be played, often creating material that is empty from an at-the-table perspective and even, through its emphasis on aesthetics, a hindrance to people actually trying to game with it.

At its start of the OSR, the only real difference between the old-school and the OSR was chronological, an arbitrary gap in between like-minded, linked content. When misconceptions and divergences occurred, the OSR base worked to counter them, perhaps the best example being T. Foster's Five Things That Need Saying, on K&K in 2009. But the size of the influx of new fans and the inability to reach everyone involved with just one or two sets of forum posts as one could just a few years prior meant that this was not very successful. By 2012, the idea that the old-school and the OSR were perhaps fundamentally different entities began to take root.

|

| Dragonsfoot, Nov 2012. Click to enlarge. |

|

| Dragonsfoot, Nov 2012 |

|

| An important caveat. Dragonsfoot, Nov 2012. |

D&D but Better and Principles Über Alles

Divergent or not, the OSR remained rooted in a solid TSR-era base mechanically. LotFP changing its spell list or the base AC, or Swords & Wizardry moving to a single saving throw type--these weren't meaningful changes in a larger categorical sense. However, the success of the retroclone movement, with its ability to resurrect

long-neglected rules engines, very early on encouraged an expansion of efforts

along those lines, with retroclones being released that were entirely separate from D&D. GORE (a clone of BRP, 2007); DoubleZero (James Bond, 2007), Four Color System (Marvel Superheroes, 2007); ZeFRS (TSR Conan, 2007); OpenQuest (RuneQuest, 2010); and The Fantasy Quest, Warriors & Wizards, and Legends of the Ancient World

(The Fantasy Trip, all 2010ish) built off of the success of games like

BFRPG and OSRIC, with a focus on their own preferred engines. However, none

of these captured the imagination in the same way, being based on far

less popular game systems. They also had a significant philosophical divergence, in that they were focused on making a dead game available once more, rather than in resurrecting a style of play that had been lost through iteration in an otherwise living game. However, they introduced the idea that maybe the OSR did not need to be all about D&D, and resulted in even OSR fans arguing over this. It was a small argument initially, since the games in question didn't have much of a following, but that too was about to change.

With these games came a sense that you didn't need old-school rules engines to truly capture the old-school experience. As long as you gave some sort of attention to tracking consumables and encumbrance, didn't have superheroic characters that were never intended to face meaningful threats, and concentrated on the dungeon, you too could be old-school. The often-touted advantage to such games was in their modern rules approach, the ability to apply everything game designers had developed since 1981 to the problem of how to create a smooth-running, intuitive, streamlined dungeoncrawl experience. While neither Dungeon World nor Torchbearer are normally seen as OSR of any stripe, their debt to it is clear, and I think it fair to say that they marked the birth of the NSR.

The problem, as the original OSR players saw it, was that they weren't looking for new games that were "D&D but better", beyond perhaps a certain amount of houseruling that every DM worth their salt did anyways (an arbitrary boundary, but one generally understood within the community, occasional flamewars around perceived heresy aside). They had embraced old-school gaming because it did pretty much exactly what they wanted; they liked D&D. In that light, "D&D but better but also not D&D" was a contradiction in terms. No matter how cleanly written and smooth-running your game, or what novel new things it did, if it wasn't D&D or very close to it, it wasn't what they were interested in: games that claimed to run on the principles of old-school D&D without using its rules were missing the point. Some OSR players did wind up running both types of games, because these new games definitely had something to offer (again, let's try and avoid the idea that there are only good games all on one side and bad games all on the other here), but there was apparently little in the way of crossing over from the initial OSR to new games like Torchbearer; again, new generations of players were the ones picking this material up.

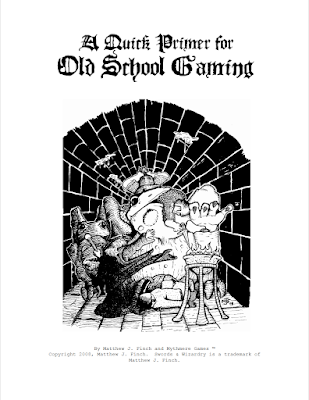

With this divorce from Dungeons & Dragons as a rules engine came the idea of universalizing the concept of OSR play. A focus on distilling a set of core principles had been with the OSR since almost the beginning, with Matt Finch's A Quick Primer for Old School Gaming (2008) starting the trend. In his primer, Finch identified four key principles he saw as essential to the old-school D&D experience: "rulings, not rules", "player skill, not character abilities", "heroic, not superheroic", and "forget game balance".

The first two in particular caught the imagination of the OSR community and became endlessly reiterated on blogs, newer primers and the like. This could lead to distortions, as people began using them in a cargo-cult fashion. For example, "rulings, not rules" was meant to explain that old-school D&D used neither universal skills nor a universal task resolution system, thus necessitating the players and DM to collectively negotiate the way the campaign handled many given tasks on a situational basis (see Part II for more on this). That having been said, D&D could be quite rigorous in its rules, becoming very specific when its designers felt that such an approach was necessary, as with dungeon exploration or elements of combat. As blogger Trollsmyth's A Theoretical Framework for the OSR explained, such rules as existed in D&D almost always had a good reason behind them (though they could also be awkward implementations, and frequently what the reason was wasn't obvious to a modern audience).[14] Finch's principle was not a call to avoid detailing key procedures, toss aside the rules that did exist, or just wing things in general, and doing so would wind up cutting away much of what made old-school D&D so distinct. Ultimately (and through no fault of his own), Finch's primer proved to be somewhat of a game-design Pandora's Box, releasing a host of readily memeable and mantra'd principles onto the world that were very easy to strip of vital context. It also inadvertently set loose the idea that principles might be all that you needed to be old-school, or perhaps could be divorced from their original context entirely--D&D--and applied to game design in general (the latter being true at least in part, but also inevitably an approach that would created different kinds of games and thus different OSRs).

Related, one supposed core OSR principle that Finch never outlined and the original OSR in general never considered key was "rules-light game design". Originally a comparative label used by the OSR in specific reference to the extreme crunchiness of the then-current third and fourth editions of D&D, rather than a principle that stood on its own, the idea that "rules-light" was an essential or perhaps even the defining quality of old-school play appeared quite early on.

|

| RPGNet, July 2009. The rules-light phenomena has already begun showing up as a concept intrinsic to defining "old-school". |

Rules-light became incorrectly applied as a supposed sacred tenet of the OSR as a whole by 2013, moving over time from explaining a type of freeform adjudication to primarily an idea about page-count: your game was "rules-light" if it had relatively few pages in its rulebook. That this supposed tenet would invalidate AD&D 1st edition, a game that could hardly be called light in most cases and yet was the pre-eminent old-school edition, only speaks to how divorced from old-school origins those that popularized this principle were. This non-existent generalized tenet was in turn adopted as a justification for increasingly thin rulesets that left out more and more of the central old-school gameplay loop in the name of reducing complexity and page count, a zebra's tail wagging the dog.[15]

|

| RPGNet, May 2013. The belief in inaccurate principles also leads to confusion over things like just how internally coherent the OSR is. |

The rise of these D&D-ish games left a sour taste in the mouth of many old-schoolers, who soon came to use terms like "streamlining" and "rules-light" with a heavy dose of sarcasm, feeling that such principles created games that smoothed so much of the classic D&D experience away that they were no more old-school than 4th edition D&D, regardless of how much the games referenced dungeoncrawling or their designers reminisced about playing BECMI back in the day. The label "OSR" grew increasingly amorphous, as the movement became more and more reduced to a series of fortune-cookie-style aphorisms like "rulings, not rules" often devoid of any context.[16] Ideas such as resource management were evermore abstracted or went by the wayside as "needless cruft", mirroring the decline of old-school principles in D&D itself.

|

| A 2015 blogpost illustrating how the focus moved from a solidly understood ruleset and gameplay effects entirely derived from it, to supposedly universal principles with a specific de-emphasis on systemic matters. The entry concludes with the idea that 5th edition is better at running an old-school game than actual old-school games. |

The OSR early on took minor side treks down science fiction roads, the sword and planet roots of D&D making such exploration reasonably natural, building new games by slapping TSR-era rules engines onto SF settings (2008's Mutant Future, a riff on Gamma World / Metamorphosis Alpha, being an early example, but 2010's Stars Without Number easily being the dominant one, "a retro science fiction role playing game" often referred to as OSR, but described by its creator as simply "influenced by the Old School Renaissance").[17] However, between the appearance of non-TSR-based clones, the move into non-fantasy settings, and the social and rules mechanics fragmentations described above, "OSR" eventually became a label applied to almost any sort of RPG.

|

| Credit to Melan.[18] |

|

| Reddit, r/osr, 2021 |

With its once-firm criteria stripped away, all that was left to guide people was the rather vague name of the movement itself, which only led to further confusion. Having lost the knowledge that "old-school" was merely shorthand for "old D&D", people began wrangling over the definition of "old-school" in a chronological sense, completely isolated from either compatibility or principles.

|

| Reddit, r/osr, 2018 |

"Old-School" was very clear when used in its original context, in the places where it was born: there was no need to specify "Old-School D&D" because that was obvious, any more than you would feel the need to add "Ford" to the name of a Ford-based movement about old Fords on a Ford forum: it could be taken for granted. However, after some 15 years of playing Telephone across multiple social media outlets, each time seeing various core components of the OSR stripped away, it's created a lot of vagueness and even hostility, as gamers sensitive to being ostracized and ignorant of the movement's history treat being presented with the original definition of OSR as an exclusionary effort attempting to take ownership of the concept of "old-school" in general. The result is that when someone tells another that no, Traveller or RuneQuest or Rolemaster or whatever is not OSR, the person being told doesn't hear "that's not an accurate label for those; this is no judgement of the quality of these games; arbitrary dates alone are no rung on which to hang a design movement". Instead they hear "I am declaring this game you like to be insufficiently old-school", with the implication that old-school equals authentic, and not-old-school equals shallow/bad. It's an emotional response, one born out of a focus on the "old-school" part of "OSR" without any understanding of what the label was actually meant to refer to. The person pointing out that perhaps discussions of old Nissans, no matter how capable or how aged a vehicle they are, don't belong on a forum for old Fords becomes that most dreaded of elitist figures: the gatekeeper.

|

| Pictured: a grog gatekeeper |

The Commercial OSR

Lastly, commodification of the term "OSR" also contributed to the confusion. Noble Knight added an OSR category in 2009, and Lulu opened an OSR storefront that same year. Similarly, RPGNow/DriveThruRPG added their own old-school category, rapidly featuring hundreds of items.

|

| Daniel Proctor, May 2009 |

Unfortunately, these places were self-policing. It wasn't reasonable to expect retailers to inspect the contents of each product tagged as "OSR" by its creator to ensure that it used gold for XP or avoided skill challenges or what have you. However, this rapidly led to a glut of product produced by the clueless and the shameless, only further reinforcing the growing perception that "OSR" was whatever people felt like. There was nothing preventing anyone from taking the most railroaded, plot-heavy quest to save the princess or a RPG about roller-skating or what have you and slapping a "OSR" tag on it. This in turn led to the creation of the Commercial OSR, referenced at the start of this post.[19]

Conclusion

G+ was killed off by Google in April 2019, and the current OSR social media environment is ... not so good. It would be naive to pretend that politics and the OSR had never intermeshed before, but the increasing politicization of 2016 and beyond has firmly extended to hobby spaces. Today, new OSR spaces are regularly filtered around political and social stances, through a combination of deliberate exclusion of elements perceived as bad and departures based on an inability to coexist with people of different ideologies. For example, the major Discord and Facebook OSR groups are run by what are often labelled "zoomers" and "pink-hairs" (and with a focus almost entirely on NSR). The old-school forums in return are the domain of "boomers" and "fascists". Ideas are filtered based on the beliefs and practices of their creators.

|

| Reddit, r/osr, 2021 |

No one platform has arisen with the popularity G+ once had to replace it. Combined with formats that hinder

searching and archiving (Facebook, Discord, 4chan, Reddit, MeWe), you

get active communities but representing fractions of the user base and

with very little in the way of ancestral memory. Questions are answered, and then

disappear into the aether. Ideas appear, and then vanish, even if

good, and interactions that once occurred between disparate

designers are often walled off. The movement as a whole continues to

thrive in terms of

numbers and day-to-day interactions, but the facilitation and

cross-pollination of ideas has certainly been stunted. At the same

time, to claim that the OSR has ground to a halt is just simple doomsaying, and new and exciting releases still occur.

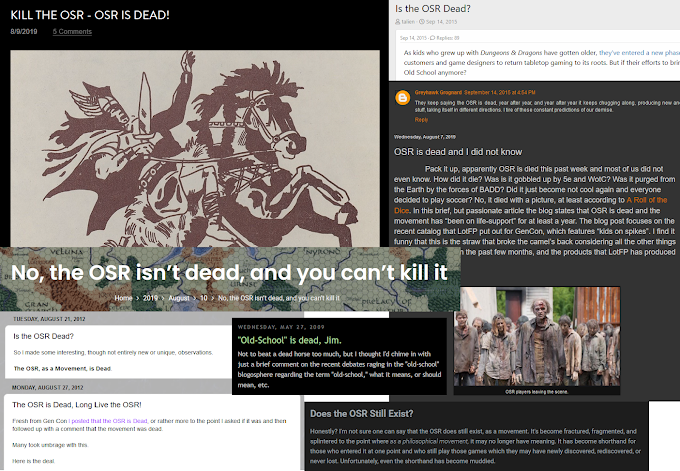

A rite of passage for old-school bloggers seems to be generating the proof for Betteridge's Law of Headlines that is a "Is the OSR Dead" post (or its rebuttal), but over at Beyond Fomalhaut a 2019 post along these lines contained a very solid summation of the state of things:

So it actually happened. The old-school community split this year, and its surviving pieces have gone their separate ways. It is gone. There has been surprisingly little talk about it, and most still speak in terms of a general scene, but in my eyes, the divorce has clearly taken place. The fault lines had been present for a few years, and the conflicts were visible for all to see. Google+’s shuttering by its corporate overlords provided a good opportunity for things to come apart, but it has also obscured the OSR’s disintegration.

[...]

What exist now are separated communities which have increasingly little in common, and do less and less communication as time progresses. There will always be individual connections, and some people will doubtless remain involved in both spheres. Things are never tidy and clear-cut. But there is no big tent “old school community” in the way there was one on Dragonsfoot ca. 2004-2008, the blogs ca. 2007-2012, or G+ for a few years afterwards. These will be smaller groups with more focused interests.

—Melan / Gabor Lux, August 2019[20]

One of my questions at the start of this post was "well, how did we get here?" Old-school D&D players

didn't set out to exclude anyone when they birthed what became known as

the OSR. However, neither did they think about including everyone, any more than a travel guide to Bulgaria includes all countries.

They were D&D players, interested in reviving a very specific,

relatively narrow part of the D&D experience. Essentially, the same growth

phenomenon that occurred with TSR-era D&D occurred in the OSR.

Growth brings new blood, but it usually arrives with a very

surface-level understanding. Given enough

new blood at once, assimilation cannot keep up and the environment

begins to change based on the pressures, active and passive, exerted by

the flood of new arrivals. This in turn generates resentment on both

sides: the original group is put off by the newcomers' assumptions,

which the OG crowd sees as shallow or outright wrong, while the newcomers are annoyed by the

original group resisting experimentation and largely insisting that things are fine the way they are. This

dynamic is all the stronger in a movement dedicated to preserving or

reviving an older thing against clear, very real examples of unwelcome

change. Like TSR, the OSR became a victim of its own success.

At

the same time, this only applies from an internal cohesiveness

standpoint. A great deal of new and interesting work came out of this

newer school, and dismissing non-Classic OSR games simply because "they're not D&D" is, unless D&D is the only RPG you care about, missing the point and ignoring their actual qualities: part of moving away from the OSR means that a game deserves to be taken on its own terms. The trouble, if it can be called that, was in still

applying the label of OSR to such games, which by implication implied that they

still meshed with old-school D&D and the work of the early revivalists.

Essentially, many members of the OSR tried to have their cake and eat it

too: the cachet (such as it was) of old-school bonafides, with the

ability to innovate and break free of perceived old-school cruft and

silliness and do something different. As many old-school players would frustratingly point out,

however, many of these innovations hadn't been ignored, but were specifically rejected or never even considered because they were so obviously contrary to old-school

principles.

So, do I think there's any value in

applying the OSR label to anything other than Classic OSR? No. At the

risk of being prescriptivist, words mean things; after a certain

point, the movement devolved into a vague conceptual slurry of "anything

I feel is OSR is OSR", and I seriously wonder at why people are determined to embrace a movement and label that they might in the same breath argue cannot be defined. That's not to knock some of the games and

supporting material that came out of this (some of which achieves what

it sets out to do quite admirably), only the increasing organizing

uselessness of the term compared with its original, clear definition. But at the risk of being

descriptivist, "OSR" is now a label being used to fit all sorts of

disparate things and there's no sense in trying to pretend otherwise:

you're not getting that djinn back in the lamp. My hope is that

eventually the various groups break away enough and clear labels

develop that each of the four (okay, the three--the Commercial leeches

will always be there muddying up things) will be easily identifiable

without histories such as this and able to do their own thing without irrelevant ideas from one group being knowingly or unknowingly glommed onto another.

[1] This is broad, since RPGs were freeform in nature, and so even such a limited definition still leaves a great deal of room for variety: tone, setting, technology level, emphasis on the dungeon vs other adventure settings, core vs. peripheral fictional inspirations, etc. And yet here we already come to a fork in the road. There is a significant core of old-school players that felt that the only true old-school D&D was what they regularly refer to as Gygaxian D&D, which is to say OD&D, Holmes, and 1st edition AD&D; left out would be B/X and the rest of the post-Holmes Basic line, anything for 1st edition released after Unearthed Arcana (with even that book given the side-eye), and 2nd edition anything whatsoever. These would be, for the most part, the players that were least happy with the OSR in general and the ascendancy of B/X as the preferred edition of OSR gamers in particular, and absolutely contemptuous of anything remotely NSR. As an aside, the caveat given here "as its original designers intended it to be played" is a key one: a lot of people who take issue with the OSR argue that the idea of a single universal "back in the day" playstyle shared amongst its scattered playerbase is a myth. Of course they're right, which is why no one who knows anything about the original old-school environment actually makes that claim, but as it's a common charge given weight by a few overzealous OSR converts I feel it's important to be specific.

[2] "Two years down the road" edit: I originally used "Nu-OSR" as the term for this style of play, a label I saw in use by

fans of these sorts of games (presumably as a sort of ironic pre-emptive attack

on charges concerning the group's false/ersatz nature compared to

stricter adherents to the OSR) and which I snagged under the principle that

it's always better to use what people are calling themselves than

inventing some new term. But along those lines, the term hasn't really developed legs and

insofar as there can be said to be a unified community of this kind,

the New School Revolution

is probably the best example and "NSR" a better label (and one now far more regularly used by adherents): an attempt to carve out a unique design

space that acknowledges the debt to the OSR but that at the same time

clearly marks itself as something of its own (and without any perceived

disparagement in the title). If you're interested in actual dialogue with these folks, you probably don't want to be calling it Nu-OSR. As such, I've altered the original wording and just added this note in the interests of preserving the snapshot of time in

which this was originally written.

[3] The hacks in particular can cut and change so much that they straddle NSR territory. For example, in addition to all of the cuts Knave implements, it's also a classless game. Similarly, while S&W Light is incredibly chopped down (4 pages), it's intended as an introduction for the full S&W system, which is unquestionably Classic OSR. Ultimately no single set of categories I create is going to work 100%, but I think it captures the most important qualities well enough.

[4] At

the same time it's easy to overstate this: one of the major impetuses

for 1st edition AD&D and one of the reasons the old-school movement

died out is how vague, incomplete, scattered, and at times outright

absent the information on what the game as a whole was meant to do and

how it intended for you to do it: plenty of rules, but nowhere near as

much guidance in terms of implementation. As I've mentioned previously,

the old-school died under the watch of gamers with 1st edition DMGs

clasped to their chests.

[5] A snapshot of the most popular OSR blogs of December 2010 can be found in this Cyclopeatron post. The blog ran monthly assessments of the state of the OSR blog scene by way of follower rankings from late 2010 to mid-2011. Philotomy's OD&D Musings, a webpage rather than a blog, was also highly influential.

[6] Sword & sorcery fiction was already a good forty years old by the time it was replaced as the leading form of fantasy fiction by the enormous success of The Sword of Shanarra in 1977 and was creatively exhausted. Additionally, the mid-70s shift from taut novels in the 160-180 page range to doorstoppers as a result of changing publisher trends was not kind to S&S, which really worked best at shorter lengths. Part of the shift in D&D from S&S to the heroic quest style of play was a mirroring of what was going on in the wider world of fantasy literature as a whole.

[7] Raggi did of course eventually come out with his own game, Lamentations of the Flame Princess, in 2010 (revised into the Grindhouse edition in 2011), a B/X derivative heralded for its solid encumbrance system and innovative approach to the thief, amongst other things. What I find most interesting about the system is how little it goes out of its way to support the sort of weird / horror gaming that it aims to facilitate. Unlike Call of Cthulhu, it is content to leave that to the DM and the adventure being played rather than attempting systemic mechanical support.

[8] Politics were banned at both Dragonsfoot and K&K not because everyone agreed but because forumgoers argued so much whenever the topic came up. While old-school D&D players are indeed mostly old white guys and often have old white-guy politics (what I've seen described as "Boomer conservatism"), the perceived "fascist" bias of the old-school by some is largely an invention of a recent crop of young left-wing Twitter types who, equipped only with a Marxist hammer, see everything as kulak nails.

[9] If you liked that kind of thing. The aesthetic preferences of this newer, younger group of players, which often tended towards the abstract, helped brand this school as "artpunk", usually not in a favourable way. Old-schoolers praised the less trained and more unconventional stylings of artists like Trampier and Otus over the photorealism of Elmore and Caldwell, but this appreciation for the unusual often did not extend to the experimentalism favoured by people like Zak S (who tended to do his own art) and Scrap Princess.

[10] Certainly one of the great gifts of the OSR, especially in its later period, has been an increased emphasis on layout, readability and usability, fully taking advantage of how the design of rulebooks has advanced and what desktop publishing software allows you to do compared to old-style (literal) cut-and-paste layout. There has also been an emphasis on writing in a way that cuts the fat, emphasizes key points, and properly organizes the flow of information. Old-School Essentials is probably the biggest recent example of a clean layout style here, with a heavy emphasis on bullet points and gradients in particular that has proven quite influential in a short period of time. My only quibble is that, if anything, there has been in some cases too much of an emphasis on reducing information, to the point that the negative effects of the "rules-light" phenomena have been somewhat mirrored in terms of text. In its worst examples we're seeing a sort of textual disintegration, where much of the potential flavour and atmosphere of a text that enthuses the reader and helps a DM understand the tone and environment is being sacrificed in the name of ruthless efficiency. While more focused on adventures than rulesets, Melan's excellent article "OSR Module O1: Against the Ultra-Minimalism" is definitely worth a read.

[11] For Zak's own definition of DIY D&D and some insight into his thoughts on design, see this 2014 interview.

[12] Patrick Stuart and Scrap Princess are probably the apotheosis of this style, with Scrap's art style as seen in Veins of the Earth and Deep Carbon Observatory often parodied by the more traditional OSR. The image given from Veins of the Earth is a Scrap Princess piece.

[13] Dungeon World co-designer Adam Koebel has spoken often of his fondness for B/X and ran a group through Keep on the Borderlands using it as part of a video series for Roll20.

[14] Also sometimes summed up online as Gygax's Fence, a riff on Chesterton's attack on ill-informed reform that was termed Chesterton's Fence.

[15]

The rise to dominance of B/X over the crunchier AD&D as the favoured ruleset of

the OSR no doubt contributed to the idea that rules-light was an

essential principle.

[16] The best attempt at producing a systemless collection of OSR aphorisms is 2018's Principia Apocrypha, which while it won't teach you to play old-school D&D will almost certainly help your DMing if you're new to it.

[17] See also 2009's Hideouts & Hoodlums, a Swords & Wizardry game reworked for Gangbusters-style play, or 2012's Blood & Bullets, for Old West games in the spirit of TSR's Boot Hill.

[18] I see that MoRB has evolved into something that no longer mentions the OSR and now features a fabulous trashy 50s-60s-style sleaze cover. https://rosevillebeach.carrd.co/

[19] As of this writing DriveThru lists almost 8,500 products bearing the "OSR" tag. Daniel Proctor's view of the OSR's then-future was rather prescient, as the interview he mentions in the screenshot (Knockspell magazine #2, May 2009, p. 32) shows. "Currently, many people (not all) have at least some fuzzy idea about what “old-school” means, which has some overlap between people. I think as time goes on the term “old-school” will be co-opted ever more for other games, since this term is seen as a desirable characteristic of games in the broader market. The “commodity” of old-school really began in the heyday of 3e, when “old-school” was advertised as desirable in 3e products. So I see this desirability transferring to just about anything and it will become more of a marketing term than anything else."

[20] I was also fond of EOTB's summational effort over at Chronicled Scribblings of the Internant Overlord, but I'm at 10,000 words as it is.

[21]

Retrocloners--whether strict clones or LotFP-style small-scale

modifications--appear to be generally fewer in number today, with the important exception of the enormously successful Old-School Essentials. WotC making legal PDFs of some of the old-school rulesets available,

and then Print on Demand versions of AD&D starting in 2017 and the Rules Cyclopedia in 2018, no doubt contributed to this. In any case, retrocloners have no single social media space.

This is an impressive amount of information. I'm going to split it up into multiple readings. Thanks for taking the time to research this and share it with us.

ReplyDeleteA fine Essay, and nail on the head for pinning Raggi/Zak as midwives for the new era, and Zak for Artpunk in particular. I think most OSR-ites and affiliates would balk at the notion of Dungeon World (or for that matter, Zweihander) as OSR, but I understand why it is mentioned since it is a fine example of something that is NOT truly OSR, but it might not be immediately obvious why.

ReplyDeleteA fair point: I've clarified their inclusion a touch with a couple of edits. Thanks for reading.

DeleteThe OSR discord (I myself got off and then onto the OSR at different points, and ended up in the Nu-SR crowd) has a whole channel dedicated to PbtA games - these days many in that space treat OSR as just another label for 'indie'

DeleteSpeaking as a Classicist-type grognard who has been on this ride since it began, I have to say… no arguments. Everything in this rather exhaustive history largely comports with my own memories and experiences. (If I were writing something like this, I'd come to the same conclusions and cite a lot of the same evidence, but - due entirely to a personal bias towards such - I'd probably put more emphasis on the small strain on retro-clones that kept faithful to the D&D rules engine but moved it into other genres, like sci-fi and western and so forth. Such games have been around since at least 2008 and even have a pre-OSR antecedent in "Mazes & Minotaurs" - which really deserves to be mentioned alongside "HackMaster" and "Castles & Crusades" as one of the movement's forerunners.)

ReplyDeleteI was aware of Mazes & Monsters, but somehow it entirely slipped my mind when I wrote Part IV. I'm going to rectify that now, if only with a footnote. Thanks for the comment, and for staying until the end.

Delete👍

DeleteDUDE! Imma gonna have to go back are reread this over and over! This is such a great historical document of the OSR. Possibly the best one out there!

ReplyDeleteGreat series of commentaries, you nailed it. I wasn’t ‘there’, spiritually at least or as an active participant in blogs or in social media, but I never saw it as a ‘movement’, OSR always just stood for ‘Old School Rules’ to me, and had nothing to do with a ‘revival’ or ‘renaissance’. It was just people maintaining and supporting old school D&D.

ReplyDeleteI remember this comment by Ben Milton on his Questing Beast channel reviewing an OSR product, and he said ‘This is not really OSR, this is just Old School’. And by that he seemed to imply that his understanding of what the OSR was aligned more with how the ‘Nu-OSR’ saw the OSR, in that the OSR was primarily about people making new games only linked tangentially to old D&D by either its principles and gaming style, or by some general similarities with some of its mechanics. I feel that with the current meaningless of the term OSR, the real old schoolers participating in the old forums (ODD74, K&K, DF) who were in it for 1e, OD&D and B/X to a lesser extent, should just adopt the term ‘OS’ and let the younger generation run with OSR. That might at least give some clarity to the situation: OS = supporting and playing old versions of D&D (TSR era if you like) and OSR = games inspired by or derivative in some way of older versions of D&D.

Just my 2 worthless cents.

Nu-SR seems to have taken the helm of your description of the OSR. The term OSR itself (particularly the discord and subreddit) in reality now seem to be more of a hanging out space for 'indie' gamers. Plenty of in-depth storygame, one-off (Lazers & Feelings), and modern game design discussion going on there.

DeleteThis is a good post, even if I'm not sure I agree with everything. For example, if the original renaissance did start with old D&D games and retroclones as opposed to 3E, there's definitely value in branding "OSR" the retroclones of games from the same era with similar design philosophies -- I'm obviously thinking of Gamma World which is just a TSR D&D reskinned for gonzo post-apocalypse, or Classic Traveller which started as OD&D houserules and has almost a stronger emphasis on player skill.

ReplyDeleteI also think that the delineation between your three types of OSR isn't that clear-cut. For example, Into the ODD can perfectly run classic D&D modules with minimal adjustments, it streamlines the experience more than it transforms it, in my opinion.

Two other points.

First, I think you really underestimate the role played by blogs (and Blogger ones in particular). A lot of the reflections on those 2004-2008 blogs are absolutely seminal, and really helped define it, both cementing and popularizing the OSR... all while opening the road for its expansion. As of today, they're still a very important matrix of new ideas and analyses, and I'd argue they're the real resilient network upon which the OSR rests and remembers its history. More than the grognard forums which are narrower in scope, and than social networks which are, as you noted, much more impermanent.

Final point, reading your article leaves the impression -- tell me if I'm mistaken -- that the expansion of the OSR is somehow a bad thing. To me, to a certain extent, it's not : such is the process and fate of any artistic movement, after all. I see value in resurrecting or retrocloning non-D&D games of the '70s-80s if you feel the same enthusiasm and nostalgia others did with OD&D, or in trying to tweak and create new rules to approach or enhance the old school experience. And I see value in calling it OSR, since it's, to me, the same ethos.

(Also also : the so-called "old school experience" was itself so varied and changing and forgetful of its origins, even by the end of the '70s, that the main traits seem to be, to me, the DIY enthusiasm and the taste for adventure and old fantasy, SF and other fantastic fiction.)

The stuff that goes "too far", for me, or off the tracks, is the commercial OSR you describe and certain franges of what I call the "provocative punk" or "edgypunk".

"For example, if the original renaissance did start with old D&D games and retroclones as opposed to 3E, there's definitely value in branding "OSR" the retroclones of games from the same era with similar design philosophies -- I'm obviously thinking of Gamma World which is just a TSR D&D reskinned for gonzo post-apocalypse, or Classic Traveller which started as OD&D houserules and has almost a stronger emphasis on player skill."

DeleteI can see that to some degree, though I'd speak of the retroclone movement more than I would the OSR because OSR was (originally) so specific and so much more successful than any of the other retroclone movements that it really deserves to be spoken of in its own light. Much of what has been written on the OSR doesn't make sense if you start trying to apply it to Traveller or what have you, games which have their own unique design assumptions over and above the stylistic and genre differences.

As for blogs, I agree with you as to their enormous importance, which is why I took the time to give everyone a chance to see the key ones. The reason they didn't get more time in the narrative is that this post is primarily focused on high-level change, and while the blogs introduced a lot of great material (seriously people, go read them), they didn't really result in the OSR drifting away from its roots much, other than the shift in centre of gravity they produced (which I did cover). I think there's definitely room for a blog greatest hits post that reintroduces some great posts to a modern audience; I may do that later, so thanks for the idea.

As for my opinion on the expansion of the OSR, I'm mixed. I like old D&D and its direct variants, so having other games come along and succeed in that space to the point that people often think that the OSR has little to nothing to do with D&D is somewhat galling. But ultimately I get really annoyed by "one true way" posting and I have no interest in saying that many of the games I mention, which have obviously succeeded on their own terms and have thriving player bases, are somehow objectively bad just because they came from muddled roots. My primary complaint is over the design muddle, bad history, and conceptual falsehoods that have resulted; in terms of games my main ire is reserved for "Old D&D but better but remove most everything that makes old D&D old D&D" games. For the most part, I would say that the concept of what "OSR" having changed is neither good nor bad; it just is, again beyond the confusion that has resulted.

Cheers.

Your post keep constantly popping back to the top of recent posts on RPG planet, often after days or weeks. Maybe you submitted the RSS feed for comments instead of the feed for new posts. You shpuld get that rectified.

ReplyDeleteThank you for the note. It's been a while, but IIRC you just give the host your URL and he does the rest, so I have no idea what could be happening there. All the same, I've sent him a mail with your comment and asked him to take a look. Thanks.

DeleteIt turns out that his software bumps any post that has been updated. As I regularly update even my oldest posts, but especially these History posts as new info comes in, that's an issue (though most of that is done with now). He's looking into it. Thanks for raising this.

DeleteYou interrupt your scholarly style (even a mention of G.K. Chesterton) to give a well merited lambasting of Commercial OSR. That raised more than a smile.

ReplyDeletePerhaps the health of the OSR should be judged by the quality of its output: by this yardstick things are going well. (Regarding your well argued footnote [9], I would say authors should write according to their talents: if you can inspire the referee with evocative descriptions, do so; otherwise OSE minimalism will do.) But maybe the fragmentation you described will mean superior work could go unnoticed outside a small group.

I agree that the health of the OSR is to some degree indicated by the number of people who want to jump on its bandwagon. At the same time, the ease with which you can just add the OSR tag while you're adding your other tags to your new product I think means that a lot of it is now pro forma, sort of a "who else can I sell this to...right, don't forget OSR".

DeleteAs for minimalism, I don't think it's entirely a matter of people writing to their talents but following perceived principles. Certainly not everyone can be evocative: that's a skill. But a reaction against the wall of text-style of adventure writing created a counterstyle focused on saying less is more, and as is so often the case with the OSR, an original principle with specific context became fetishized into a general principle so that the means became an end unto itself. People have to work at getting that minimal; I would say almost no one is going to write in a sort of Shatnerian broken style by nature. If you look at the recent No Artpunk contest held by PrinceofNothing, in some ways Trent Foster's entry sticks out the most because he more than any of the others actually uses sentences as the basis of his adventure construction. However, I don't want to come across as too strident here: in general I favour minimalism more than wordiness and think that an emphasis on lean and mean has been one of the great gifts the OSR has given us (though as with many things, it takes its cue from the original terseness of Gygax, Bledsaw et al).

Thanks for the kind comments on the various posts you made.

I thought Raggi lives in Finland?

ReplyDeleteHe does. Not sure why I wrote Sweden; maybe I found a source that mentioned he moved there first. I'll double-check that; thanks.

DeleteVery nicely done!

ReplyDeleteThanks for this series. I came into D&D when 2E was new, left when 3E went min a direction I disliked and went backwards to older editions, settling on “classic” non-advanced D&D. I kept up with the earlier stages of the OSR, lost track of it during the Google+ era, and when I came back to it wanting to run some online games during COVID, I had missed a lot. You filled that in excellently. FWIW, I use Black Hack rules as it feels like 12 year old me playing AD&D 2 and forgetting or fudging the stuff I found too complicated to be fun - but i a, running a sandbox in the JG Wilderlands. Newer “streamlined” rules helping me explore more old-school content than I ever have before, running 3 weekly sessions for almost 2 years.

ReplyDeleteI must say that I enjoyed that. Not only well-researched but well-written as well. That's my 2008 DF post noting the explosion of the simaculara and the splintering of the already small pool of Old School gamers. At the time, I was part of DF's web team and the most active Mod. We were under a barrage of requests to sliver the "1st Edition" and "Classic D&D" fora down into sub-forums to accommodate the clones. How quaint that all seems now. I wonder where it ends (cue Dr. Manhattan, "Noting ever ends."); it does seem -from an admittedly small sample- that more and more products are "system agnostic" now, intended to be played with nearly any system.

ReplyDeleteThis entire series is an incredibly well-written history; I can't begin to comment on the events themselves because I wasn't there, and my own weird niche of "written in Pathfinder, reviewed and purchased by OSR, played heavily by 5e people" isn't even remotely intersecting with most of these threads. Still, I think this is an engaging and fascinating treatment with a genuine historian's eye and that's a rare accomplishment indeed.

ReplyDeleteVery good, thanks for such an exhaustive and researched series! This is all really useful for a relative newcomer, and with link rot and general discordance, this helps tie the strange and esoteric roots together.

ReplyDeleteThese are some excellent posts!

ReplyDeleteI have to say the whole discussion of what constitutes OSR reminds me a huge amount of Roguelike video games. There's the exact same split with old school principles and concepts vs. new technologies and game mechanics. It's almost comically similar.

I agree with the other comments that these are excellent posts. I think you are missing one thing and could be your next post in the series and that’s the relationship between 5E and the OSR. That can encompass everything from Zak S and Pundit being consultants and the controversy of such in 2018 or so. Many of the Nu-OSR systems you mention blend B/X mechanics with 5E. You talk about the commercial OSR but there is also the phenomenon of OSR game publishers releasing 5E material, in some cases just 5E conversions of originally OSR products (e.g., adventure modules). The popularity of Goodman Games’ Original Adventures Reincarnated also seems relevant. You could also go into the current controversies with the direction WotC is taking with 5E (i.e., alignment, race vs. ancestry, the disclaimer on TSR-era products on DTRPG, etc.)

ReplyDeleteI wouldn't want to move too far into the realm of 5th edition: that's current events, not the habitat of the historian. It also I think by nature would demand more opinion: we know less about what has recently happened and what still is happening. So while overall I find the idea intriguing, I think I'll take a pass until 5th ed is dead and buried and I can accurately put a capstone on things. Thanks.

DeleteI finally (finally!) had a chance to read this entire series last weekend, but I didn't have the time to pen my comments. Now...4-5 days later, I've forgotten at least part of what I wanted to write. Probably needs a re-read to refresh the ol' memory banks.

ReplyDeleteHowever: well done! This is good stuff, both accurate (as far as I can tell) and intensely interesting. It is also (IMO) rather useful at entangling the web of just what "OSR" is, and the various meanings and connotations the term has taken to mean.

One (well, two) important events you are leaving out of your history are the deaths of Gary Gygax (March 2008) and Dave Arneson (April 2009) in quick succession. I think the IMPACT of their deaths, especially Gygax (who was the better known of the two) caused a tremendous surge in fueling the OSR "movement." People began reflecting, reminiscing, and rediscovering these "old games" (even as they contemplated their own mortalities and link to the gaming hobby). My blog...which you kindly mention above as a "mover & shaker"...was only begun in June of 2009 AFTER I had discovered OTHER Old School blogs like Grognardia, Sham, Black Dougal, etc. and found that I, too, had something to express with regard to old time role-playing. I was not a member of the the popular forums (DF, etc.) at the time...rather, I came from an indie-design space (The Forge), and only began looking into these games (again) as I contemplated my own history with Gygax, Dungeons & Dragons, and other early (TSR) works...histories I found echoed in the thoughts of other bloggers.

The blog community acted in many ways as an "uber-forum;" we were all reading each others' posts, commenting on them, riffing off them for our own blogs. Many writing projects (which would eventually become recognizable books, clones, zines, adventures of the OSR) came out of back-and-forth discourses on these blogs. Certainly, my own books did. We encouraged each other, we inspired each other, and (eventually) we MONETIZED each other...this networking being our best (or, in some cases, ONLY) form of marketing our products.

Once the market was there, others jumped in.

Anyway, good stuff here Keith. Probably Part V is ripe to be broken into a two or three part series of its own documenting the post-founder (Gygax/Arneson) era. The pertinent "ages" that follow would probably go along these lines:

- the Blog Age

- the G+ Age

- the Post-G+ Age (i.e. the Balkanization of the OSR)

Personally, I think that tracing all these various lines and strands of cultural development are fascinating, especially when compared side-by-side with other world events (the Trump movement in the USA, the COVID pandemic, etc.).

I think the 4E-Pathfinder-5E history is worth noting, too, though I see it as all (or mostly) corporate driven, which is why WotC is so slow to keep up with morphing/mutation of the D&D/OSR sub-culture and its interests. How much 5E's recent developments parallels that of the OSR, and the importance/function of pop culture (including streaming series like Critical Role) in feeding that development is also an interesting line of query/study.

Cheers, man. Good work!

: )